If there are any limits to a president’s power, it wasn’t evident from Donald Trump’s speech before a joint session of Congress on March 4, 2025.

In that speech, the first before lawmakers of Trump’s second term, the president declared vast accomplishments during the brief six weeks of his presidency. He claimed to have “brought back free speech” to the country. He declared that there were only two sexes, “male and female.” He reminded the audience that he had unilaterally renamed an international body of water as well as the country’s tallest mountain.

“Our country is on the verge of a comeback the likes of which the world has never witnessed, and perhaps will never witness again,” Trump asserted.

The extravagant claims appear to match Trump’s view of the presidency – one virtually kinglike in its unilateral power.

It’s true that the U.S. Constitution’s crucial section about the executive branch, Article 2, does not grant the president unlimited power. But it does make this figure the sole “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States.”

This monopoly on the use of force is one way Trump could support his 2019 claim that he can do “whatever I want as President.”

Before Trump’s speech, protesters outside had taken issue with Trump’s wielding of such unchecked power. One protester’s sign said, “We the People don’t want false kings in our house.”

With those words, she echoed a concern about presidential power that originated more than 200 years ago.

AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana

Remnants of the monarchy

When the Constitution was written, many people – from those who drafted the document to those who read it – believed that endowing the president with such powers was dangerous.

Ratified after a lot of huffing and puffing, on May 29, 1790, by rather nervous citizens, the text of the Constitution had stirred many controversies.

It wasn’t just the oftentimes vague language, which includes head-scratchers such as the very preamble, “We the People of the United States.” Nor was the discomfort due solely to the document’s jarring brevity – at 4,543 words, the U.S. Constitution is the shortest written Constitution of any major nation in the world.

No, what made that document especially problematic, to borrow from John Adams, was that it provided for “a monarchical Republick, or if you will a limited Monarchy.”

Adams would eventually become the nation’s second president in 1797. Even though he was a staunch supporter of the Constitution, he was honest enough to take a hard look over the political layout of the new nation. And what he found were remnants of the British monarchy and traces of a king whose unchecked abuses had led the Colonists to demand their independence in the first place.

“The Name of President,” Adams couldn’t help concluding in a letter to prominent Massachusetts lawyer William Tudor, “does not alter the Nature of his office nor diminish the Regal Authorities and Powers which appear clearly in the Writing.”

Stock Montage/Archive photos, Getty Images

While Adams was only somewhat uncomfortable, as a historian of the early republic I can stress that other observers at the time were downright appalled.

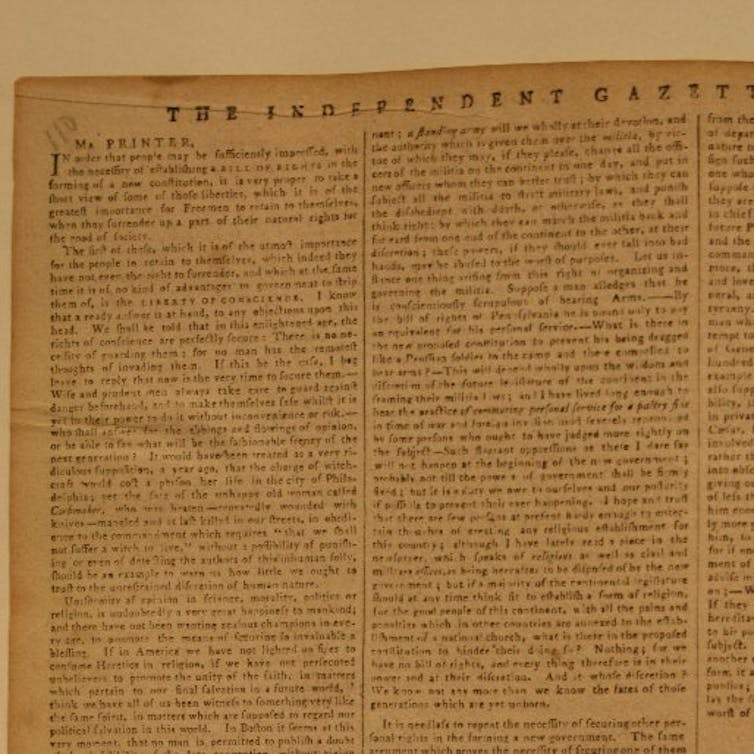

In a 1787 article published in the Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer, “An Old Whig” – identity unknown – wrote, “The office of President of the United States appears to me to be clothed with such powers as are dangerous.”

As the commander in chief of the Army, the American president “is in reality to be a king as much a King as the King of Great Britain, and a King too of the worst kind – an elective King.”

Consequently, as the author of this article resolved, “I shall despair of any happiness in the United States” until this office is “reduced to a lower pitch of power.”

‘Subjects of a military king’

Concern over a commander in chief declaring martial law, no matter the legality of the measure, was similarly on the minds of the Americans who had read the Constitution.

In 1788, a patriot who went under the pseudonym of “Philadelphiensis” – real name, Benjamin Workman – issued a sweeping warning. Should the president decide to impose martial law, “your character of free citizens” would be “changed to that of the subjects of a military king.”

A president turned military king could “wantonly inflict the most disgraceful punishment on a peaceable citizen,” the piece continued, “under pretence of disobedience, or the smallest neglect of militia duty.”

New York Public Library, Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

Another power given to the president was also universally considered extremely dangerous: that of granting pardons to individuals guilty of treason.

Maryland Attorney General Luther Martin reasoned that the treason most likely to take place was “that in which the president himself might be engaged.” What the president would do, Martin wrote, would be “to secure from punishment the creatures of his ambition, the associates and abettors of his treasonable practices, by granting them pardons.”

George Mason, who participated in the Constitutional Convention and also drafted Virginia’s state Constitution, foresaw a gloomy scenario. He shivered at the idea of a president who would “screen from punishment those whom he had secretly instigated to commit the crime, and thereby prevent a discovery of his own guilt.”

Choosing ‘villains or fools’

The framers did limit executive power in one significant way: The president of the United States is subject to impeachment and, upon conviction of treason or other high crimes, removal from office.

But in the meantime, the president may enact irreparable damage.

The Constitution was finally ratified – but only begrudgingly by the American citizens, who feared a president’s abuse of power. More persuasive than the legal restraints placed on the office, the belief that the people would choose their leader wisely tipped the scale toward approval.

Delegate John Dickinson asked a rhetorical question: “Will a virtuous and sensible people chuse villains or fools for their officers?”

Also, 18th-century common sense deemed it improbable that a person without virtue and magnanimity would run for the nation’s highest office. Americans’ faith in their first president, the upstanding George Washington, helped convince them that all would end well and their Constitution would be sufficient to protect the republic.

The Federalist Papers, the 85 essays written to persuade voters to support ratification, were suffused with this optimism.

People “of the character marked out for that of the President of the United States” were widely available, said the Federalist #67.

“It will not be too strong to say,” reads Federalist #68, “that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue.”

ConSource

Government of laws?

Adams wasn’t so optimistic. He wavered. And then he flipped the issue on its head.

“There must be a positive Passion for the public good … established in the Minds of the People,” he had written in a 1776 letter, “or there can be no Republican Government, nor any real liberty.”

After almost 250 years of uninterrupted republican life, Americans are used to thinking that their nation is secured by checks and balances. As Adams kept repeating, America aims at becoming “a government of laws, and not of men.”

Americans, in other words, have long believed it is their institutions that make the nation. But the opposite is true: The people are the soul and the conscience of the republic.

Everything, in the end, boils down to the character of these people and the control they assert over who becomes their most important leader.