Vice President Kamala Harris has offered an ambitious plan to build more: “Right now, a serious housing shortage is part of what is driving up cost,” she said last month in Las Vegas. “So we will cut the red tape and work with the private sector to build 3 million new homes.” Included in her proposals is a $40 billion innovation fund to support housing construction.

Former president Donald Trump, meanwhile, has also called for cutting regulations but mostly emphasizes a far different way to tackle the housing crunch: mass deportation of the immigrants he says are flooding the country, and whose need for housing he claims is responsible for the huge jump in prices. (While a few studies show some local impact on the cost of housing from immigration in general, the effect is relatively small, and there is no plausible economic scenario in which the number of immigrants over the last few years accounts for the magnitude of the increase in home prices and rents across much of the country.)

The opposing views offered by Trump and Harris have implications not only for how we try to lower home prices but for how we view the importance of building. Moreover, this attention on the housing crisis also reveals a broader issue with the construction industry at large: This sector has been tech-averse for decades, and it has become less productive over the past 50 years.

The reason for the current rise in the cost of housing is clear to most economists: a lack of supply. Simply put, we don’t build enough houses and apartments, and we haven’t for years. Depending on how you count it, the US has a shortage of around 1.2 million to more than 5.5 million single-family houses.

Permitting delays and strict zoning rules create huge obstacles to building more and faster—as do other widely recognized issues, like the political power of NIMBY activists across the country and an ongoing shortage of skilled workers. But there is also another, less talked-about problem that’s plaguing the industry: We’re not very efficient at building, and we seem somehow to be getting worse.

Together these forces have made it more expensive to build houses, leading to increases in prices. Albert Saiz, a professor of urban economics and real estate at MIT, calculates that construction costs account for more than two-thirds of the price of a new house in much of the country, including the Southwest and West, where much of the building is happening. Even in places like California and New England, where land is extremely expensive, construction accounts for 40% to 60% of value of a new home, according to Saiz.

Part of the problem, Saiz says, is that “if you go to any construction site, you’ll see the same methods used 30 years ago.”

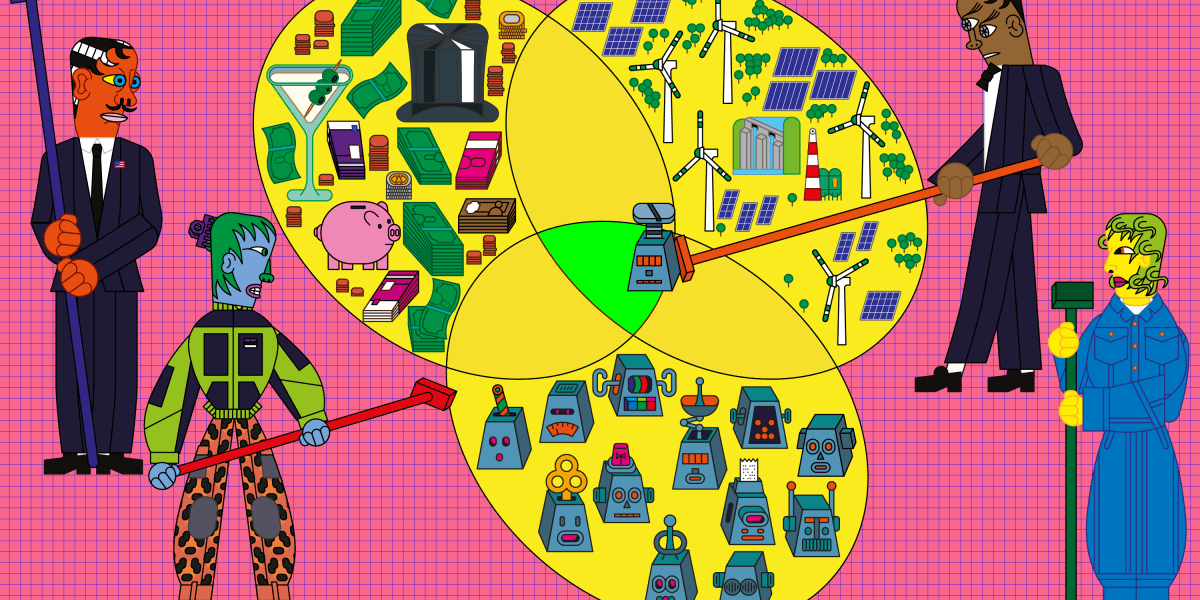

The productivity woes are evident across the construction industry, not just in the housing sector. From clean-energy advocates dreaming of renewables and an expanded power grid to tech companies racing to add data centers, everyone seems to agree: We need to build more and do it quickly. The practical reality, though, is that it costs more, and takes more time, to construct anything.