The selection of Tim Walz as Kamala Harris’ running mate has sparked a wave of commentary suggesting that simply by elevating a former small-town football coach to the candidacy for vice president, Democrats will naturally secure the allegiance of rural voters nationwide.

At first glance, such analysis – tinged with wishful thinking – seems self-evident. Walz, the governor of Minnesota, was raised in a small, rural town in Nebraska and runs a Midwestern state with a strong rural identity. And it is hard to deny that many rural advocates and writers genuinely feel seen and represented with the choice of Walz – a feeling not felt in quite some time. Indeed, you can now sport a Harris-Walz camo hat this hunting season.

But a closer examination reveals that such expectations may be overly simplistic and optimistic.

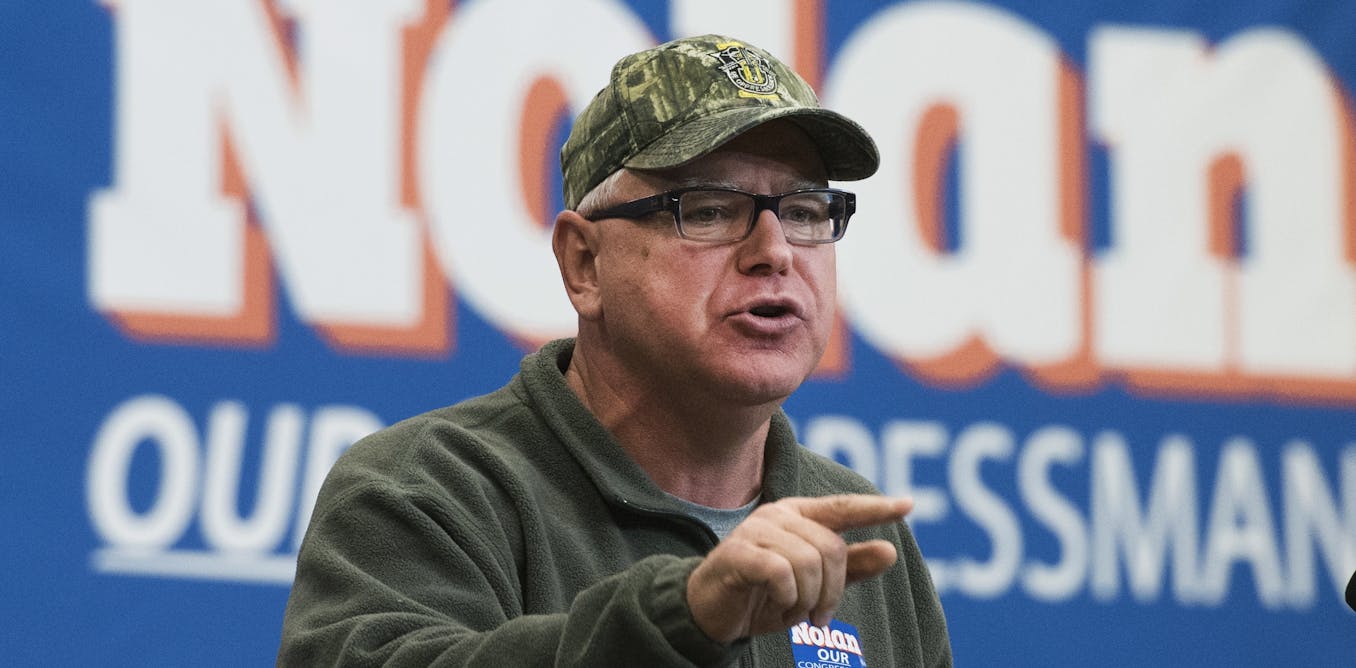

Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Getty Images

Nationalization of the rural voter

While Walz’s selection may offer symbolic value, it demands a lot of a single candidate to overcome a seismic restructuring of American political geography. Over the past 40 years, as political scientist Dan Shea and I show in our book “The Rural Voter,” Republican partisans have come to dominate rural politics.

In one respect, Walz has built his career trying to reverse that tide, advocating for communities like the one he came from. His positions are, of course, open to interpretation, but Walz has had to grapple with what we call the “nationalization” of the rural voting bloc – the fact that rural voters in all parts of the country view themselves as politically powerless, victims of bad government policy and culturally maligned.

While images of corn dog-eating, dad-joking, “Midwestern Nice” folksiness have become routine in covering Walz, they do little to explain the real issues that have made rural voters a sizable force in recent American elections.

Over the past 40 years, this politicized identity has come to distinguish rural voters from urban ones, and even from other groups that are predisposed to vote for Republican or conservative candidates. Drawing on a nationally representative sample of 7,500 rural voters from February 2024, I joined 15 other scholars in digging into these views.

“Midwestern Nice” does little to capture the grievance and anxiety felt by many rural residents living across the country. As multiple indicators suggest, majorities of rural residents think their communities get less government spending than they deserve, that local kids will not do as well as their parents later in life, and that much of this is the fault of urbanites. On this front, the Midwest is no different than the rest of the country.

Limited success in rural contests

Given the fact that rural voters in the Midwest are much like the rest of the country, Walz’s performance within his home state of Minnesota is a relevant bellwether for his national appeal among rural voters. Though Walz has deep rural roots, rural voters have not always supported him as much as his backstory might quickly suggest.

In six elections over the past eight years, populist candidates for major offices in upper Midwestern states have seen differing levels of success in rural parts of their districts or states. Using the vote share that each candidate received from majority-rural counties – counties where the rural population is more than 50% of the total – as a proxy for rural support both district- and statewide, Walz’s performance has decreased among rural voters since he last ran for reelection to Congress in 2016. It does not exceed the support other candidates in the Midwest received from similar rural-majority counties.

I calculated the percent of the population living in a census-defined rural bloc for Walz’s former congressional district and the state of Minnesota. I then calculated the percent of Walz’s vote share that came from rural-majority counties in each of his past three elections, one for Congress and the other two for governor.

Like other Democrats in districts across the nation, Walz struggled to win rural voters in his congressional district – Minnesota’s First District – and statewide. Neither of those are majority-rural constituencies, but even when just looking at the most rural areas, Walz never won a majority. In fact, his largest losses running for reelection as governor in 2022 were in rural communities. That year, Walz captured just 38% of the vote in rural-majority counties across Minnesota.

Some might see this as evidence that no Democrat could do well in rural America. If not the folksy Walz, then who, they might ask?

Just look next door.

In Walz’s own Midwest region, other Democrats have performed strongly among rural constituencies. U.S. Sens. Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota performed nearly as strong as their Republican opponents within the most rural parts of their electorate. Even Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer outperformed Walz’s rural numbers.

That’s right, if Democrats wanted a candidate from the Midwest on the national ticket who did better with rural voters, Harris-Whitmer would have a better track record of rural support. And worth noting: Whitmer, Baldwin and Klobuchar each grew up in cities.

Managing Democrats’ expectations

None of this is to say that Democrats have made a mistake by playing into the rural or small-town trope that many have enthusiastically conjured over Walz’s candidacy. Walz is a clear counterbalance to the image constructed by another Midwestern, self-proclaimed spokesperson for rural America on the ballot: JD Vance.

A recent Washington Post poll on the two vice presidential nominees’ popularity shows that Walz has secured a marginal geographic advantage among voters across the U.S. In urban areas, about 20% of voters dislike Vance more than like him. Among rural respondents, just 14% of voters dislike Walz more than like him. Walz, however, is still less popular than popular among rural voters, while Vance is viewed favorably, on average.

But it is worth remembering that the most popular candidate to ever win rural America neither hails from a rural America nor pretends to. Donald Trump’s appeal lies not in his personal connection to rural life but in his ability to tap into the sentiments of rural discontent and align them with his broader political message. Trump has shown that the politics of rural identity do not easily translate to simple identity politics.

It should not be hard to find a candidate who won’t disdain rural voters as a basket of deplorables, as Hillary Clinton famously did in the 2016 presidential campaign. Nor should it be hard to find a candidate who believes that showing up in rural areas is not just good strategy but good for democracy.

But Walz’s challenge is not merely to present a rural-friendly image.

It’s addressing the deeper issues that motivate rural voters, such as economic insecurity, perceived cultural marginalization and distrust in government. Symbolic gestures – and camo hats – alone are not sufficient to sway their support.