Charles Kingley was a widower and a single father of four who lived in the Northern Liberties neighborhood of Philadelphia in 1829. He worked at a brewhouse but struggled to secure care for his youngest child, William, who was about 5 years old and nearly blind.

Barbra Sion, a 74-year-old woman living in Southwark, was recorded by welfare officials as “old, sickly, cared for by an adopted child.”

In order to remain in their homes and care for their loved ones, both Philadelphians sought financial support through the Guardians of the Poor, the elected government officials who managed local welfare programs. But in the 1810s and 1820s, these pensions came under suspicion in Philadelphia. Were families like the Kingleys or the Sions really deserving of support, or were they faking it?

As a scholar of early American history, a historian of disability and a disabled individual, I am acutely attuned to arguments about disability spanning the founding of the U.S. to the present day. While researching the daily experiences of disabled Philadelphians in the early 1800s, I discovered the records of the Guardians of the Poor at the Philadelphia City Archives.

In my research, published in the spring 2024 issue of the Journal of the Early Republic, I explore how and why the Guardians of the Poor, alongside other welfare reformers, began rationing care and outlawing pensions.

Guardians of the Poor

In the early 1800s, Philadelphia, like most early American cities, had a diversified welfare state.

The Guardians of the Poor levied poor taxes on every home. They used this money to purchase everyday goods such as firewood, food and clothing for the poor, and also to distribute weekly pensions to families in need.

They also supported public institutions like the Philadelphia Almshouse, which provided shelter and met the basic needs for the city’s poorest people. And they purchased spots in the Pennsylvania Hospital, where they referred poor people for medical care.

While the almshouse and hospital were important sites of healing, many disabled households relied on the pension system. Pensioners could get health care in their homes, delivered by physicians hired by the Guardians of the Poor. When provided supplemental income, they could continue working and living independently.

John T. Bowen/Library of Congress/World Digital Library

Rising poverty, deepening resentment

Like most Eastern Seaboard cities in the early 1800s, Philadelphia was home to thousands of immigrants and a growing free Black community. It was also experiencing rising unemployment and vagrancy rates, debts from the War of 1812 against Great Britain, and inflation from the Panic of 1819.

As more people fell into poverty, more people appealed to the local welfare officials for support.

Taxpayers, meanwhile, bemoaned the rising costs of welfare, especially the pension system. Why would anyone work, they asked, if the government was just handing out money? Were people really unable to work, or were they just fooling the Guardians of the Poor? There was a pervasive sense that scammers were bleeding coffers dry.

In 1817, a citizen group called the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Public Economy launched an investigation into the system. It sent a survey to charities and government officials asking, “What do the poor allege as the cause of their poverty?”

The charities and officials reported back: “In most instances want of employment is the alleged cause…[A]lthough this may temporarily operate, idleness, intemperance, and sickness are the most frequently the real causes.”

The citizen committee’s report concluded that “the people of colour; the lower classes of Irish emigrants; the intemperate and day labourers” were wasting taxpayer dollars.

Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Public Economy

While the committee at times highlighted gender wage gaps, high costs of living and other real challenges, it focused foremost on individual behaviors and personal choice. Poor people, the authors believed, were being reckless with their money: They gambled, hired sex workers and drank themselves into poverty.

The report sparked a series of further investigations. In 1821, a state committee was founded to look into the poor laws, and in 1827 the Guardians of the Poor published the results of their own investigation.

They all echoed the same narrative: The wrong people were taking advantage of welfare.

A massive almshouse

To cure these social ills, the citizens committee proposed ending pension payments and institutionalizing the poor. Reformers argued it would be far cheaper to house the poor together, where they would be fed, clothed and housed at scale.

In Philadelphia, that meant shifting poor taxes to create the Blockley Almshouse, a 3,000-bed facility that served as an almshouse, orphanage, hospital and workhouse on the west bank of the Schuylkill River – an area that at the time was on the outskirts of the city, far from most residents’ families and communities.

In 1902, the facility was renamed Philadelphia General Hospital. It was closed in 1977 and soon thereafter leveled. Today, the space houses a range of facilities owned by the PGH Development Corp.

As the Guardians of the Poor manuscript collections held at the Philadelphia City Archives make clear, Blockley Almshouse hired medical professionals to screen those who were admitted and supposedly weed out welfare scammers from those deserving of care.

Sick and injured individuals were sent to the hospital wards, where they encountered physicians and medical students. Students at the University of Pennsylvania completed their clinical rounds at the almshouse, where they performed surgeries, concocted medications and learned how to diagnose patients.

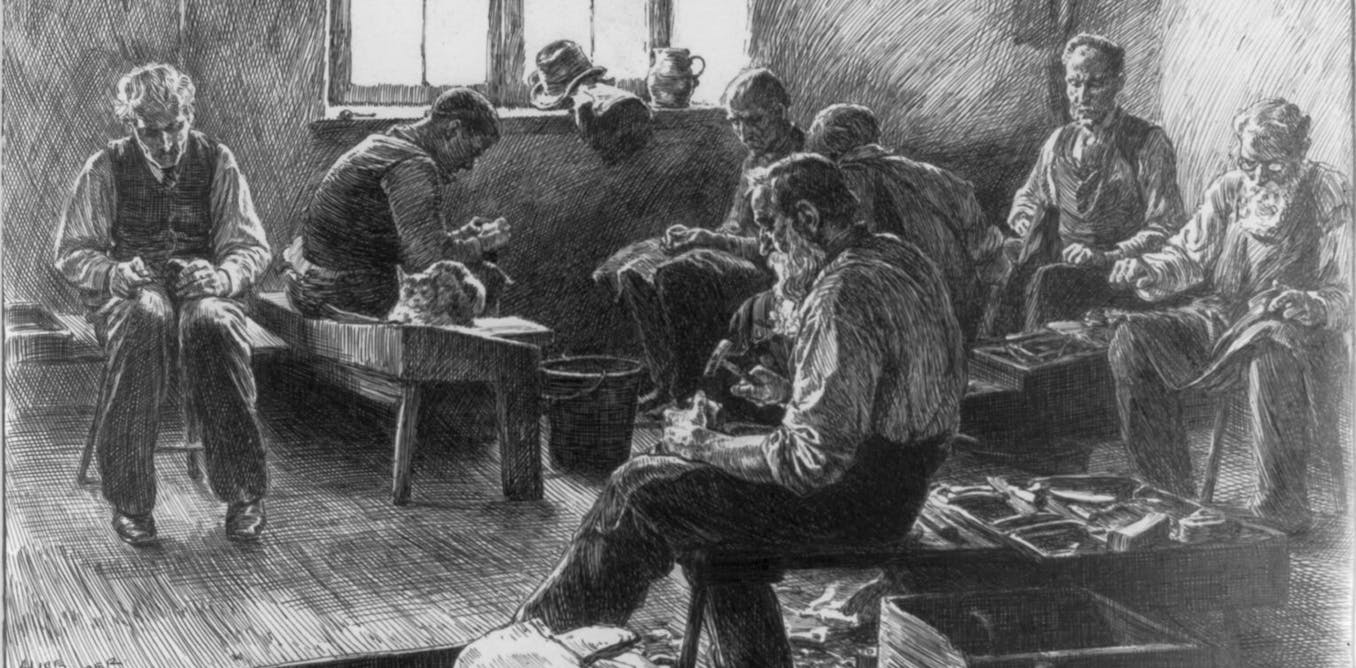

Both disabled and able-bodied poor were sent to the workhouse, where they would perform tasks such as picking oakum – in which you unravel rope into individual fibers – spooling thread, sewing clothes or making shoes. Whatever they produced was sold to local markets to fund the institution.

Reformers presumed that most people would find conditions so abhorrent at the almshouse that they would leave and find work in the city instead.

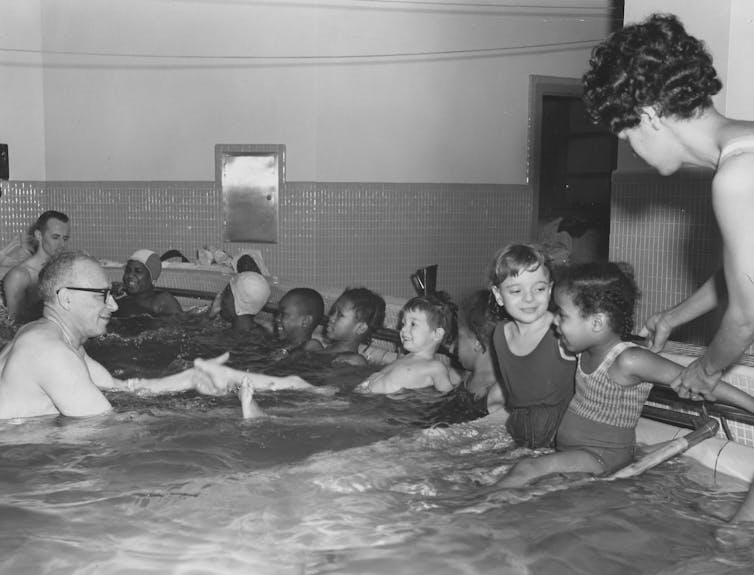

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

The so-called scammers

It’s hard to imagine what the almshouse could provide for families like the Kingleys or the Sions. These families are just two out of 656 listed in the Register of Relief Recipients maintained by the Guardians of the Poor for the year 1829.

Transcribing the record book, I found that all 656 households on the pension lists were home to single parents raising children, elderly persons, persons with disabilities, or some combination of the above. Most had lived in the city for decades.

Ironically, Blockley never turned a profit. Philadelphians continued to fund the institution through poor taxes, and the facility never broke even.

The real costs, of course, were borne by those forcibly institutionalized, separated into wards by gender and health condition, and detached from family members by the expanse of the river.

Many lived in abject poverty to escape the facility. In 1830, Mathew Carey, an economist and public figure in Philadelphia, complained that hundreds of Philadelphians who “have been gradually reduced to the most severe distress and penury – whom honourable men would shudder at seeing inmates of an alms-house, and who, in fact, would rather die than go there” deserved pension support.

The shift in welfare laws – to defund pensions and fund institutions instead – acted like a net to catch and punish people who were economically dependent. Welfare reformers could have turned an eye on employers, businesses, rental costs or other systemic drivers of poverty. Instead, they focused on supposed scammers who didn’t really exist.