But he is still busy and engaged. He and his wife, Kim, operate the DTS Charitable Foundation, which he founded in 1987 to promote a “vegetarian lifestyle, and prevention of cruelty and suffering to animals both nonhuman and human” (he has been a vegetarian for decades). Knee injuries sidelined him from basketball a few years ago, but he does freestyle figure skating and plays “extreme croquet,” which is typically played on challenging terrain without the usual out-of-bounds rules. He has a pilot’s license, and one of his current passions is designing high-performance radio-controlled airplanes. “I love it,” he says. He is mourning the loss of the “scary-fast red delta-wing airplane” that he built in 1972, flew for 52 years, and considers his favorite invention: “Unfortunately, it had an in-flight breakup earlier this year and was destroyed. I was quite crushed by that. So was the airplane, by the way.”

Scholz says he and Kim have slowly turned their house into a workshop and lab. “There is no ‘house,’” he says. “When we have someone coming over for dinner, we actually have to clear out space to have a table that we can all sit at together.” (A proclivity for making things runs in the family; his son, Jeremy Scholz ’05, majored in mechanical engineering at MIT.) Scholz does interviews in “what used to be the electronics area for troubleshooting and fixing all this stuff in my studio,” he says. “It’s become a drafting area and a radio-controlled-aircraft fabrication/assembly area, and I have a small shop in what was the furnace room.”

He still hopes to get his studio back up and running, “because I am still writing music, believe it or not, in what’s left of my brain,” he says. “And it’s very frustrating not to be able to go in and make the recording of what I hear.”

Scholz marvels that classical composers could hear everything in their heads. “You listen to Vivaldi or Bach, and you think, ‘How did he know that those violins were going to work together when they all came together at the same time?’ He could only play one,” he says. “Whereas I always had to record things, listen to them together, and then go back and … ‘Well, that was the wrong bass line! I’ll try a different one,’ and so on.”

He initially came up with this method of layering different recordings together to please himself. “When I first started doing this, I was a kid in my 20s—well, late 20s—and I was just trying to put some music down that I thought sounded good. I actually didn’t believe that anyone else would think it sounded great,” he says. When it took off commercially, he felt compelled to become a positive role model as well. “Somehow I had to make those two things coexist—you know, being a positive influence and making some awesome music that people would think was kick-ass rock and roll.”

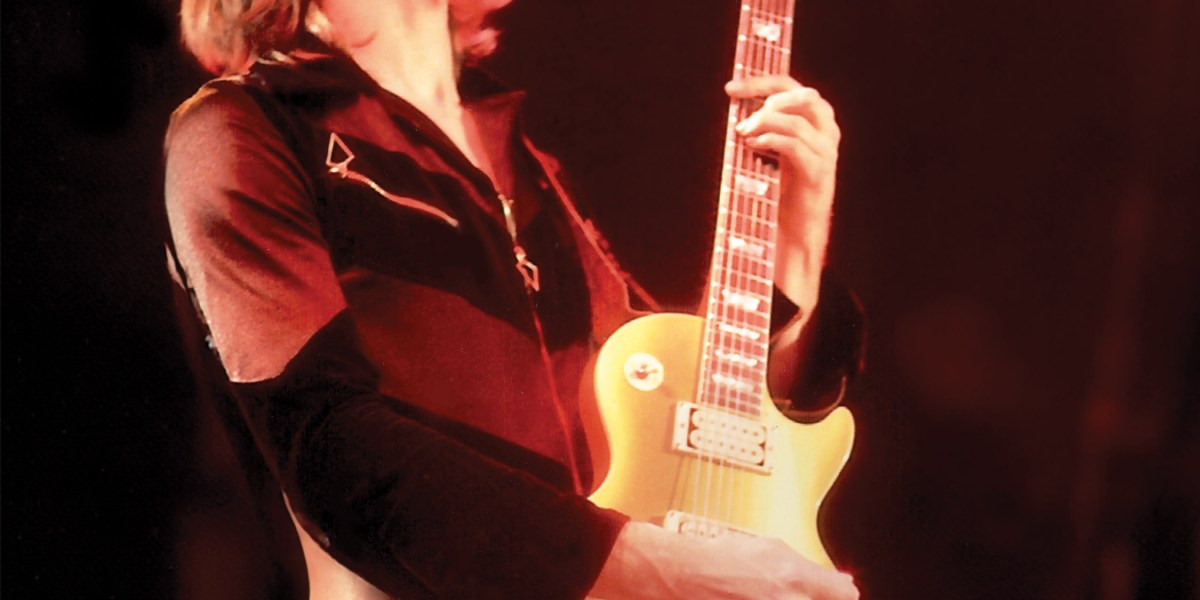

GETTY IMAGES

“After the first album, I was suddenly placed in a position where I was a figure that people were going to emulate. Kids listened to this music,” he says. “I felt this enormous weight, that everything that I did and everything that I said and anything I put on an album was going to have a possible effect on someone.”

While other rockers were cultivating wild personas, he focused on the connection between self-improvement, higher education, and Boston’s music and tried “to encourage people to do things that I thought were a good step for mankind,” he says. “So when someone 50 years later comes and says, ‘Oh, this song really helped me get through,’ it means the world to me.”

Scholz has always been true to himself and to his music, even in the days when he was being rejected by one record label after another. “Having failed miserably,” he says, “I thought, ‘You know what? I’m going to make one more demo, and it’s going to be just exactly the way I see it, and the way I want to hear it, and I’m going to play every single part.’ And that worked, oddly enough. It’s been a wild ride.”