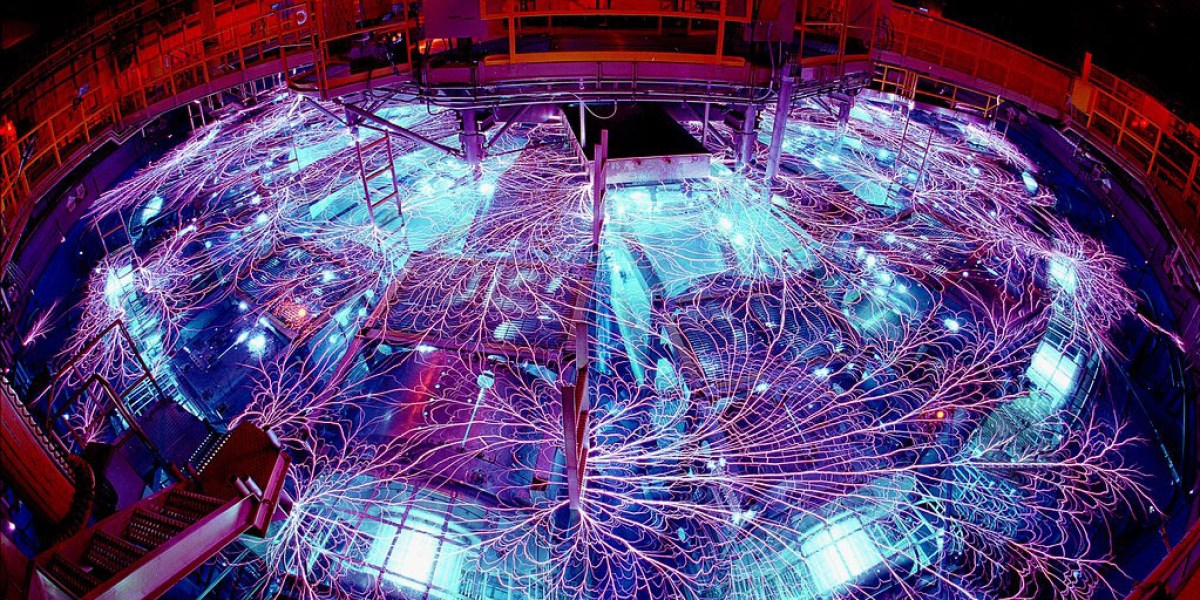

Flanked by klaxons and flashing lights, it’s an intimidating sight. “It’s the size of a building—about three stories tall,” says Moore. Every firing of the Z machine carries the energy of more than 1,000 lightning bolts, and each shot lasts a few millionths of a second: “You can’t even blink that fast.” The Z machine is named for the axis along which its energetic particles cascade, but the Z could easily stand for “Zeus.”

RANDY MONTOYA/SANDIA NATIONAL LABORATORY

The original purpose of the Z machine, whose first form was built half a century ago, was nuclear fusion research. But over time, it’s been tinkered with, upgraded, and used for all kinds of science. “The Z machine has been used to compress matter to the same densities [you’d find at] the centers of planets. And we can do experiments like that to better understand how planets form,” Moore says, as an example. And the machine’s preternatural energies could easily be used to generate x-rays—in this case, by electrifying and collapsing a cloud of argon gas.

“The idea of studying asteroid deflection is completely different for us,” says Moore. And the machine “fires just once a day,” he adds, “so all the experiments are planned more than a year in advance.” In other words, the researchers had to be near certain their one experiment would work, or they would be in for a long wait to try again—if they were permitted a second attempt.

For some time, they could not figure out how to suspend their micro-asteroids. But eventually, they found a solution: Two incredibly thin bits of aluminum foil would hold their targets in place within the Z machine’s vacuum chamber. When the x-ray blast hit them and the targets, the pieces of foil would be instantly vaporized, briefly leaving the targets suspended in the chamber and allowing them to be pushed back as if they were in space. “It’s like you wave your magic wand and it’s gone,” Moore says of the foil. He dubbed this technique “x-ray scissors.”

In July 2023, after considerable planning, the team was ready. Within the Z machine’s vacuum chamber were two fingernail-size targets—a bit of quartz and some fused silica, both frequently found on real asteroids. Nearby, a pocket of argon gas swirled away. Satisfied that the gigantic gizmo was ready, everyone left and went to stand in the control room. For a moment, it was deathly quiet.

Stand by.

Fire.

It was over before their ears could even register a metallic bang. A tempest of electricity shocked the argon gas cloud, causing it to implode; as it did, it transformed into a plasma and x-rays screamed out of it, racing toward the two targets in the chamber. The foil vanished, the surfaces of both targets erupted outward as supersonic sprays of debris, and the targets flew backward, away from the x-rays, at 160 miles per hour.

Moore wasn’t there. “I was in Spain when the experiment was run, because I was celebrating my anniversary with my wife, and there was no way I was going to miss that,” he says. But just after the Z machine was fired, one of his colleagues sent him a very concise text: IT WORKED.

“We knew right away it was a huge success,” says Moore. The implications were immediately clear. The experimental setup was complex, but they were trying to achieve something extremely fundamental: a real-world demonstration that a nuclear blast could make an object in space move.

“We’re genuinely looking at this from the standpoint of ‘This is a technology that could save lives.’”

Patrick King, a physicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, was impressed. Previously, pushing back objects using x-ray vaporization had been extremely difficult to demonstrate in the lab. “They were able to get a direct measurement of that momentum transfer,” he says, calling the x-ray scissors an “elegant” technique.