The U.S. looks set to have its first-ever Cuban American secretary of state in 2025, after President-elect Donald Trump nominated U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida for the role. But don’t expect that to mean cozier relations between Havana and Washington.

Rubio, who if confirmed by the Senate will also be the first Latino to hold the post, is one of the most hawkish members of Congress when it comes to the communist-run island. Indeed, one recent profile of Trump’s pick for top diplomat described Rubio as “Cuba’s worst nightmare.”

So how will Rubio’s antipathy for the communist government in Cuba – alongside Trump’s desire to be seen as a dealmaker – affect U.S.-Cuban ties?

As a historian of U.S.-Cuban relations, I know that ties between the two countries have been fraught for more than 60 years.

After overthrowing U.S.-supported dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959, Fidel Castro nationalized U.S.-owned property and became an ally of the Soviet Union against the United States. He also supported left-wing revolutions in Latin America and Africa,challenging U.S. global interests.

In response, successive U.S. presidents have prohibited trade with Cuba and most travel to the island by U.S. citizens since the 1960s.

There was a brief thaw in relations during the Obama administration.

But Trump reinstated the U.S.’s policy of confrontation with Cuba between 2016 to 2020 – a period marked by a tightened embargo on the island and increased rancor between Washington and Havana.

That may well happen again under Trump’s second administration – but that isn’t certain. There is also the potential for changes in U.S.-Cuban relations. Perhaps, even, there are reasons to believe the dynamic may improve.

From thaw to Cuban chill

No doubt, Trump and Rubio are critics of Havana’s communist government.

Rubio’s family emigrated from Cuba to the U.S. in the 1950s before the triumph of Castro’s revolution in 1959.

As senator, he has opposed any loosening of either the U.S. trade embargo with Cuba or travel restrictions on U.S. citizens wishing to visit the island.

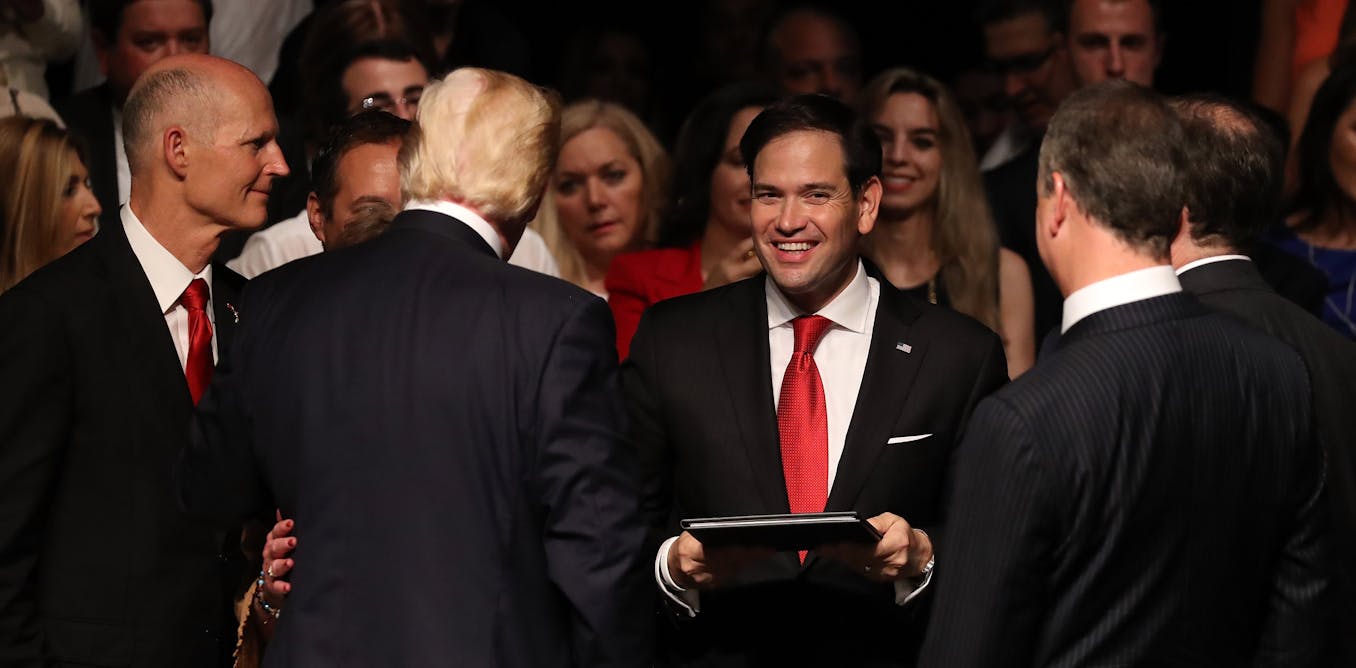

Eva Marie Uzcategui/AFP via Getty Images

When the Obama administration began establishing formal diplomatic relations with Cuba in 2014, for example, Rubio was among the plan’s most vocal critics.

As part of this thaw, President Barack Obama also loosened travel restrictions, removed Cuba from the State Department’s list of nations that sponsor terrorism, and made it easier for Americans to send money to family members in Cuba.

Trump reversed these policies after entering the White House in 2017.

Though the administration never severed diplomatic relations, Trump’s State Department essentially closed the embassy in Havana and stopped the processing of visas for Cubans wishing to travel to the U.S.

His administration also placed Cuba once more on the list of nation’s that sponsor terrorism.

Reportedly, Cuba was not high on the list of Trump’s priorities in his first term, unlike immigration. But he did wish to satisfy the demands of Rubio and his Cuban American constituents in South Florida who strongly favored a tough line against Havana.

And as a senator, Rubio has been Cuban Americans’ foremost advocate and Cuba’s principal antagonist in the U.S. Congress.

Trump’s next moves

Though his stance on Cuba was less bold than Obama’s, President Joe Biden lessened some restrictions imposed by the first Trump administration.

His administration, for example, made it easier to send money to Cuba, along with other changes ostensibly designed to support the Cuban people, not the Cuban state. The U.S. embassy also began processing visas.

The embargo, however, remained enforced and untouched.

It is reasonable to assume that Trump will reverse Biden’s tentative measures. If the past offers any guide, the American embassy may reduce its operations and with it suspend the processing of visa applications. Trump has also vowed to eliminate the humanitarian parole program through which at least 100,000 Cubans have been able to enter the U.S. legally.

But there are limits to what the Trump administration can – or feels it can – do to punish Cuba.

Despite most favoring the embargo, a large minority of the Cuban émigré community still want to send money to their families in Cuba and visit their relatives when possible.

And though a majority of Cuban Americans voted for Trump, most also want to continue humanitarian parole.

Sven Creutzmann/Mambo photo/Getty Images

Moscow’s move in Havana

But appeasing Cuban Americans is just one concern for Trump. Other geopolitical factors could also influence U.S. policy.

Russia, for example, is making increased investments in Cuba and easing its energy shortages, while reopening at least one Cold War-era base.

Given Havana’s long-standing ties with Moscow and the fact that both countries are isolated by portions of the international community, this closeness is understandable – and Trump’s stated admiration of President Vladimir Putin may mitigate concern in Washington.

China, however, would be another matter.

President Xi Jinping’s government is making investments and seeking bases in Cuba, part of a pattern of China’s increased engagement throughout Latin America.

In the past, Trump has taken pride in his willingness to challenge China. Cuba could get caught in the crossfire.

But Trump’s past dealings with another pariah state allows for the intriguing possibility of a different course on Cuba.

U.S. relations with North Korea, like those with Cuba, are a remnant of the Cold War. For better than half a century, U.S. policy has forbidden trade, travel and even diplomatic relations with the hermit kingdom, much as it has with Cuba.

But that did not stop Trump from engaging with the communist state’s leader.

During his first term, he met three times with President Kim Jong Un – in Vietnam, Singapore and even the Demilitarized Zone straddling North Korea and South Korea.

The art of the deal, Cuban-style

As the example of North Korea makes clear, Trump enjoys playing the rule-breaking dealmaker on the international stage.

He also envies Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize, which he won in 2009, stating that he believes he deserves one.

And there is a deal to be had with Havana, one that would end the U.S. embargo in return for reparations for American-based owners of property expropriated during the Cuban Revolution.

Of course, unlike North Korea, Cuba is not a nuclear power and it cannot use threats of nuclear war to bring U.S. diplomats to the table. But being so close to the Florida coast – just 90 miles away – it can use the threat of China or Russian bases as a bargaining chip.

What is more, before becoming president, Trump’s record on Cuba was inconsistent. In 1999, he condemned the late leader Fidel Castro as a dictator, but in either late 2012 or early 2013, employees of the Trump Organization reportedly visited Cuba to scout possible locations for golf courses, hotels and casinos.

While running for president in 2015, Trump stated that he was “fine” with Obama’s Cuban policy and “somewhere in the middle” between Obama and Rubio regarding Cuba.

Trump’s hard line on Cuba appeared only in September 2016, when his campaign against Hillary Clinton took him to Miami in search of Florida’s electoral votes.

A new chapter in the cold war?

Certainly for now, Havana is preparing for yet another, more disagreeable chapter in the U.S.—Cuban Cold War.

But Trump is unpredictable. Given that he will never again run for president, he has less incentive to appease Cuban Americans and instead look to secure a legacy for himself abroad. eg: “instead look” is confusing. Maybe “instead MAY look”?

Cuba watchers such as myself should at least entertain the possibility that relations between the U.S. and Cuba may be very different four years from now.