The fatal shooting of Brian Thompson, the chief executive of UnitedHealthcare, on Dec. 4, 2024, in New York City, immediately captured national attention. But many people immediately fixated mostly on the manhunt for the assailant, and then on Luigi Mangione, the 26-year-old suspect who was charged on Dec. 9 with Thompson’s murder.

Mangione, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania who worked as a software engineer, has attracted a fan base of enthusiastic and intrigued supporters. Some people have posted social media videos and posts saying they want to date Mangione and think he is good- looking. Others have focused on other personal details, like the more than US$270 backpack Mangione might have dropped in Central Park after the alleged crime.

There is also new Mangione-themed merchandise, like T-shirts, and crowdfunding campaigns to support the alleged murderer’s legal defense.

Some people have even gotten tattoos of a rendering of Mangione’s face, alongside the words “deny, defend, depose,” which were inscribed on the bullet casings found at the scene of the crime.

I am a scholar of criminal justice. Society’s fascination with certain crimes and criminals is far from new.

From infamous outlaws like Bonnie and Clyde to notorious serial killers like Ted Bundy, public attention often shifts away from the tragedy they caused and victims they hurt or killed.

Instead, many people become fascinated with the complexity of the accused.

PA Department of Corrections/Handour/Anadolu via Getty Images

Not the first alleged criminal to go viral

In the 1800s, sensational newspaper stories helped Jesse James, a notorious gang leader and robber in the American West, capture the public imagination.

Today, there is a 24-hour news cycle, with social media and streaming platforms amplifying different trends and stories. Criminals – and also those accused of crimes – now gain widespread attention through viral tweets, short-form video content and true-crime documentaries.

Part of the intrigue for viewers and readers is trying to determine, from the comfort of their own homes and screens, whether the accused is actually guilty.

In 2024, for example, Netflix released a popular documentary series about Erik and Lyle Menendez, two brothers who were sentenced to life in prison in 1994 for murdering their parents at home in 1989.

The Netflix show reignited public interest in their case, sparking a reexamination of the role that their father’s alleged sexual assault of them played in the crime.

Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón announced in October 2024 that he recommends the Menendez brothers should be resentenced for their crimes, with the potential for parole. A judge still needs to make a final decision on the case.

Mangione’s case highlights this growing trend of “armchair crime-solving,” where online observers immerse themselves in the investigative process from afar.

Some people following the Mangione case even jokingly photoshopped images of the suspect into different situations and proclaimed that they could provide an alibi for him.

Critics of glamorizing criminals argue that these crowd-driven narratives often stray far from the actual facts, risking the creation of what some experts call an “illusionary truth effect” that distorts the reality of a situation.

Bettmann/Contributor

What forms this connection

There are different reasons why people who don’t know alleged criminals, or those convicted of crimes, feel a kind of kinship with them.

First, criminals with a manifesto might tap into widespread frustrations, becoming symbols of resistance against issues or unpopular organizations like private health care companies, in Mangione’s case.

The notorious crime couple Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, known simply as Bonnie and Clyde, embodied defiance against economic inequality. They robbed banks and carried out other crimes, including murder and car theft, in the 1930s.

Although some of the crimes were violent, people romanticized the couple, casting them as folk heroes akin to modern-day Robin Hoods.

Second, crimes that draw attention to problems in society, such as corruption or inequality, often gain attention when observers’ views resonate with the alleged criminal’s stated frustrations.

When Mangione was arrested at a McDonald’s in Altoona, Pennsylvania, police found that he was allegedly carrying a pistol and a three-page statement that described the killing of Thompson as a “symbolic takedown.” It also reportedly said that the crime was a response to the health care industry’s “alleged corruption.”

Some of Mangione’s supporters have created wanted posters resembling hit lists, vilifying other health insurance executives while casting Mangione as a hero.

Bettmann/Contributor

Hey, good lookin’

Attractive criminals specifically capture people’s attention because they challenge preconceived notions of what a criminal should look like. People tend to associate negative behaviors with specific physical traits, such as appearing ugly, aggressive or unkempt.

When an alleged criminal like Mangione is perceived as good-looking, it can trigger a halo effect – or a bias in which some positive impressions, like a person’s physical appearance, influence how unrelated traits, like morality or behavior, are perceived.

The contradiction of a physically attractive person who has allegedly done ugly, violent things can complicate observers’ judgments and perceptions of guilt.

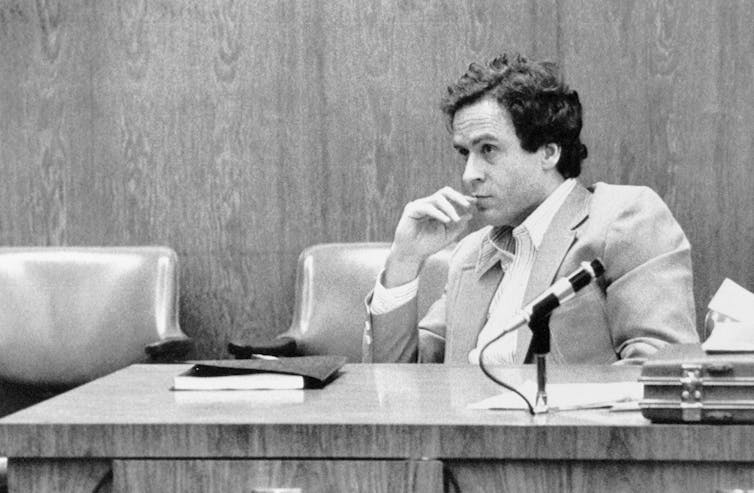

Ted Bundy, an American serial killer in the 1970s, exemplifies this type of effect. His charm and good looks allowed him to seamlessly blend into society, making it easier for him to deceive and murder dozens of women.

Bundy’s appearance and charisma not only facilitated his crimes, but they also contributed to the enduring public fascination with him – even long after his execution in 1989.

Dubbed by some as “Gen-Z’s Ted Bundy,” Mangione and his case demonstrate how people continue to grapple with their implicit biases in assessing guilt or danger.

This tendency can be partly attributed to a desire to understand and humanize criminals, which may be shaped by the “I can fix him” mentality or the savior complex, where an observer believes they can change the offender.

Ethics of glamorizing criminals

While public fascination with criminals is understandable, it raises significant ethical concerns.

One major issue is the tendency to elevate perpetrators, alleged or otherwise, at the expense of their victims. When criminals are treated like celebrities, the suffering of victims and their families is often overshadowed. This dynamic can trivialize the gravity of violence and create a warped sense of admiration for those responsible.

And nowadays, merchandise, crowdfunding for perpetrators, and sensationalized documentaries turn human tragedy into profit.