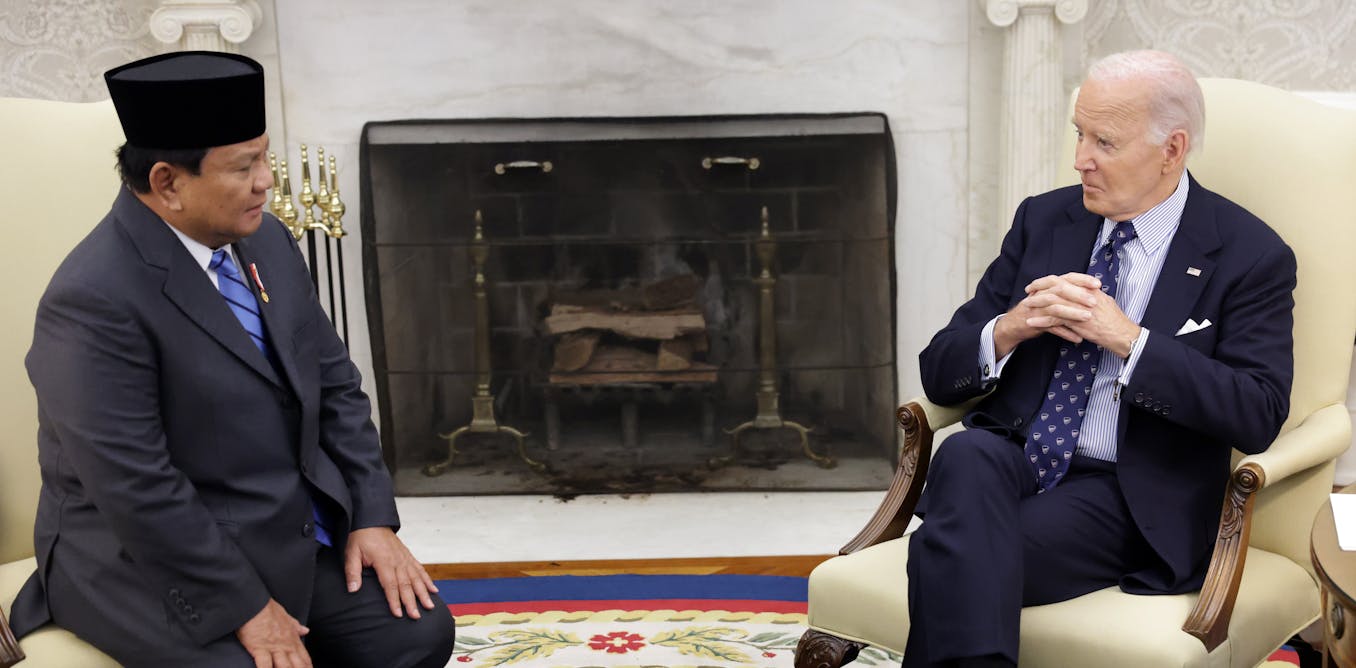

It’s been a whirlwind week for Indonesian president Prabowo Subianto. On Nov. 9, he was breaking bread with Chinese leader Xi Jinping; three days later he was sitting down with President Joe Biden in the White House. In between, Subianto found time to reach out to Donald Trump to congratulate the incoming U.S. president on his election victory.

The visits to the U.S. and China form part of a two-week overseas tour for Subianto that will also take him to Peru, Brazil and the U.K., as well as several Middle East countries.

The itinerary hints at the diplomatic priorities of the newly seated president of Southeast Asia’s biggest economy: balancing Indonesia’s relations with key members of both the West and the Global South, while seeking a more assertive leadership role in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia’s balancing act

Subianto’s back-to-back meetings with Xi and Biden highlight the role Indonesia tries to play in ensuring regional stability and security in the Indo-Pacific.

The meetings coincided with an ongoing U.S.-Indonesian marine exercise off the Indonesian island of Batam. The third annual military exercise of its kind, such maneuvers between U.S. and Southeast Asian partners have tended in the past to be framed as a countermeasure to China’s assertiveness in the contested waters of the South China Sea. But while U.S. and Indonesian marines were engaged in drills, Subianto and Xi were making nice – pledging greater maritime cooperation between the two countries.

The big question now is how a Trump White House will affect Indonesia’s balancing act on security in the Indo-Pacific region.

Trump’s Indo-Pacific strategy

Trump’s first presidency offers some clues into what his second term may look like regarding its Indo-Pacific policy. The 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report issued by the Trump administration marked China as a “revisionist” power – that is, one that is dissatisfied with the current status quo – and an aspiring regional hegemon.

To counter this, Trump adopted an “offshore balancing” strategy – in effect utilizing regional allies to keep China in check. This approach involved security pacts with traditional allies and joint military training exercises with countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia. It also included providing military equipment to partners in the region and occasional U.S. Navy “freedom of navigation” operations.

AP Photo/Andy Wong

But there was another side to Trump’s Indo-Pacific strategy. Aware of the U.S.’s lack of direct security interests in the region – no U.S. territories are threatened – but concerned that any escalation could lead to military conflict, Trump was willing to back down on potential flash points with China in the South China Sea in exchange for Beijing’s cooperation in confronting one of the region’s key threats to stability: North Korea.

These two policy tweaks under Trump’s first administration – easing pressure on Beijing in the South China Sea while outsourcing regional stability to Washington’s Indo-Pacific allies – handed to Indonesia a challenge and opportunity.

As Southeast Asia’s largest and most populous nation, Indonesia was required to show leadership in the negotiation of the code of conduct in the South China Sea as part of its key diplomatic mission to maintain regional stability.

Subianto tilts toward China

Indonesia has long been willing to shoulder the burden of managing regional security. Successive leaders have taken the role seriously, especially given the country’s constitutional mandate to pursue an “independent and active” foreign policy. Historically, this has meant Indonesian leaders avoiding being too close to either the U.S. or China in order to boost their credibility as an independent actor.

Xie Huanchi/Xinhua via Getty Images

But since Subianto was inaugurated as the president of Indonesia in October 2024, Indonesia’s foreign policy has shown a nascent shift away from the West. Days after his inauguration, Subianto sent his new foreign minister to Kazan, Russia, to attend the meeting of BRICS nations and express Indonesia’s desire to join the expanding bloc of non-Western economies.

BRICS’s largest member is China, and the group seeks to position itself as an alternative to Western security and financial architecture.

This formal expression of intent to join BRICS marks a change from policy under Subianto’s predecessor, Joko Widodo.

Furthermore, a joint statement issued during Subianto’s visit to Beijing suggests that Indonesia is starting to entertain Beijing historical maritime claims in the South China Sea.

For decades, Indonesia refused to acknowledge Beijing’s claims on rocks and atolls within Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone in the waters around Natuna – an Indonesian island that intersects with China’s “nine-dash line” denoting the area Beijing sees as Chinese.

But the joint statement issued during Subianto’s visit to Beijing stated that the two countries had reached “an important common understanding on joint development in areas of overlapping claims” that was consistent with “respective prevailing laws and regulations.”

Talk of “overlapping claims” is a departure for Indonesia and suggests that Subianto is willing to move closer to accepting the boundaries set by Beijing in the South China Sea.

OECD or BRICS? Or both?

This isn’t to say that Indonesia is cutting off its options for greater cooperation with the West, too. During the White House leg of Subianto’s visit, Biden signaled the U.S.’s strong support for Indonesia’s push to join the Western-dominated Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD membership would serves as a benchmarking platform for Indonesia, with the organization setting international standards and support for Indonesia to help attract better quality foreign investment.

BRICS membership, meanwhile, would represent more of a political and economic move that would place Indonesia alongside other countries seeking an alternative to the U.S.-dominated international institutions.

The impetus for Indonesia to join could only deepen should Trump’s plan to slap heavy tariffs on overseas goods come to fruition.

Providing cover for Subianto

Certainly, it appears that Indonesia under Subianto could develop a more pro-Beijing stance in the face of a Trump White House.

Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East are likely to take up much of Trump’s immediate attention, pushing issues such as security in Southeast Asia – and more generally in the Indo-Pacific region – further down the list.

Meanwhile, the Chinese government shows no signs of deviating from a policy that includes incremental moves to control the South China Sea and exert its economic influence on nations in Southeast Asia.

Already, some observers are questioning whether Indonesia’s shift in how disputed territory in the South China Sea is discussed is tied to economic cooperation with China that includes the US$10 billion worth of deals signed during Subianto’s Beijing visit.

And a more insular, anti-interventionalist White House under Trump could give Subianto cover to forge Indonesia’s path as a regional leader, encouraging it to do so while also developing closer economic and strategic ties to China and the Global South.