A presidential or political visit is one of the ways in which the United States marks places as uniquely important. A space meriting the pomp and circumstance that accompanies a president, or a place viewed as so particularly American that an aspiring president might want to have their picture taken there, takes on special status in American culture.

Twelve of the last 14 presidents visited Philadelphia’s Independence Hall during their political careers. American politicians often visit sites of great importance to the national character, and Independence Hall is the location of both the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the drafting of the Constitution.

The U.S. has many sacred civil spaces, places that the country looks to when celebrating or reflecting on American identity. Some of these places were established for the express purpose of serving these functions: the National Mall and the U.S. Capitol in Washington and the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, built to commemorate the country’s westward expansion.

Some of these places earn this designation through association with history: Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, sites of significant events in the American Revolution; the Pearl Harbor National Memorial, commemorating American deaths from the Japanese attack that sparked U.S. entrance into World War II; and the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where local police in 1965 attacked and bloodied civil rights protesters, who ultimately crossed the bridge two weeks later under the protection of a federal court order.

Still other places emerge through a sort of national consensus, taking on special status over time as Americans use them in ways that mark them with meaning.

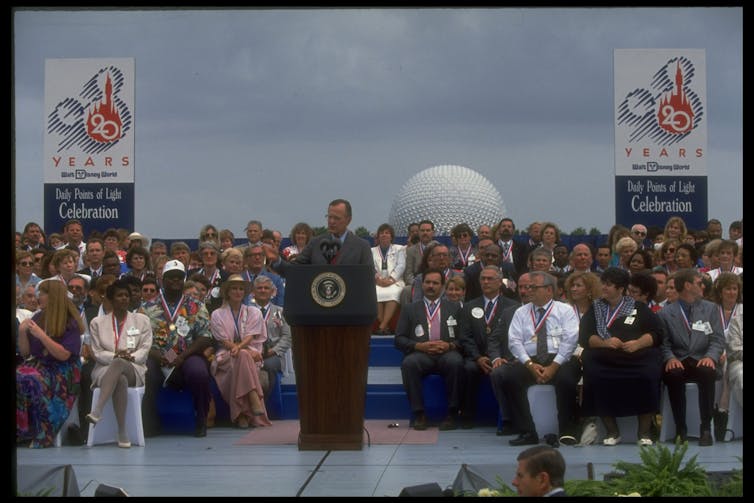

And while twelve of the last 14 presidents may have visited Independence Hall, the same 12 also visited some of the places often forgotten when accounting for holy civic sites: the Disney theme parks.

Joe Sohm, Visions of America/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Record cold and a second chance

In my book “Disney Theme Parks and America’s National Narratives: Mirror Mirror for Us All,” I explore how Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and Walt Disney World, near Orlando, Florida, have become two of the most important spaces for the celebration and creation of American identity.

One of the reasons for this is the legitimization a presidential visit bestows on a site. Forty years ago this month, Walt Disney World received a very special visitor.

In January 1985, as President Ronald Reagan prepared to take the oath of office for a second time, temperatures in the Washington area dipped to record lows. The inauguration and some related festivities were due to take place outdoors, but conditions were severe enough to cause concern for the many thousands scheduled to participate. So the usual celebrations, including the popular Inaugural Parade, were canceled in favor of a smaller event indoors.

Only a handful of the 25 high school marching bands that had traveled from places like Kentucky, Massachusetts and Michigan to play in the parade were able to perform for the president. That left thousands of students and their families disappointed.

In a presidential history first, however, the Inaugural Bands Parade would get a second chance to march outside the ceremonial space of Washington at what could be called the nation’s other capital – Walt Disney World.

In April 1985, Walt Disney World announced that it had partnered with Days Inn, Greyhound Bus Lines and Burger King to offer reduced price accommodations and food for about 4,000 students to enjoy a weekend at the theme park before performing in their own parade on Memorial Day, May 27.

Not only would the bands get to play at Disney’s Epcot Center, but they would also be able to perform for the president, who flew from Washington to be there for this special parade.

Dirck Halstead/Contributor/The Chronicle Collection, Getty Images

New site for American identity

Memorial Day, the day of the parade itself, was warm and sunny. Disney visitors thronged the 1.2-mile parade route and waved American flags as they listened to patriotic songs. The parade was watched over by the president and first lady, Nancy Reagan. The equivalent of the president and first lady of Disney, Mickey and Minnie Mouse, joined them.

This moment was remarkable for several reasons.

First, Reagan had been one of the hosts of the show “Dateline Disneyland,” the live coverage of the opening of Disneyland in 1955 only 30 years before, when no one knew he would be the nation’s 40th president.

Second, the visit marked an important moment in the recognition of the Disney theme parks as sites of American identity.

Reagan went directly from laying wreaths at Arlington National Cemetery on Memorial Day, a treasured American tradition, to an appearance at Epcot, where in an economic policy speech to the crowd, he introduced a “new American revolution.” This second American revolution was announced not in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, but at the American Adventure pavilion in Orlando.

The Reagans’ photo with Mickey – with Mickey dressed as Uncle Sam and Minnie in a colonial-style dress – captures the idea, I believe, that culturally Disney spaces are as legitimate as national parks or historic sites as places for the celebration of the American story.

As longtime Disney cast member Terry Brinkoetter remembers, presidential visits like Reagan’s affirmed Disneyland and Walt Disney World as “places where people could learn and be inspired to continue our shared journey toward a more perfect union.”

Disney parks have become stops on a secular pilgrimage made by presidents and ordinary citizens alike, places to understand what it means to be an American.