While concerns about the future of American democracy dominate headlines worldwide, millions of Texans are already seeing a rapid decline in democratic standards.

In December 2024, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued a New York doctor for prescribing abortion-inducing medications to a woman in Collin County, Texas, alleging that the shipment violated Texas’ near-total ban on abortion.

Two months earlier, Paxton’s office had sued to block a federal rule protecting women’s out-of-state medical records from criminal investigation. And in 2022, it sued the Biden administration over federal guidelines requiring doctors to perform abortions in emergency situations.

Paxton’s lawsuits – alongside the state’s restrictive abortion policies – raise troubling questions about individual privacy and women’s bodily autonomy in Texas, where I live and teach. And they’re indicative of a broader problem. As my research on democracy and human rights shows, the state government is becoming increasingly antidemocratic.

Scholars examine a number of factors to determine the health of a democracy. Elections must be free and fair. There should be freedom of expression and belief, multiple competitive political parties and minimal corruption. A democratic government must also respect individual freedom.

On many of these metrics, I believe Texas falls short.

Are Texas elections free and fair?

Texas has some of the most restrictive voting laws in the United States, including strict voter ID laws, stringent limits on mail-in and absentee ballots and no online voter registration.

Republicans, who passed each of these policies, claim their concern is a democratic one – election integrity. Yet, when Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick offered a US$25,000 reward to anyone who could prove voter fraud in the 2020 election, it led to just one arrest.

The Texas Legislature nonetheless pledged to pass an even more restrictive voting bill in 2021, referencing “purity of the ballot box,” an old Jim Crow phrase. Democratic lawmakers ended up fleeing the state to paralyze the state assembly and keep the most egregious parts of the bill from passing.

Healthy democracies also have robust competition between multiple parties so that voters have real choices at the polls.

Yet since its current constitution was written in 1876, Texas has effectively been a one-party state governed by conservatives. No Democrat has won statewide office since 1994 – the longest Democrats have been locked out of statewide office in any state.

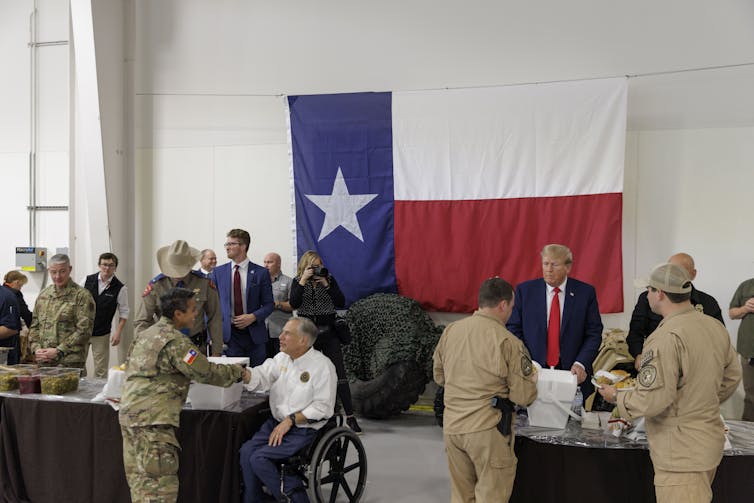

Sergio Flores/Getty Images

Money in politics

Texas puts no limits on individual campaign contributions to the governor, one of just 12 U.S. states that lacks this common anti-corruption measure.

This has allowed Texas’ current governor, Greg Abbott, who has been in office since 2015, to raise vast sums of money. In the 2022 Texas gubernatorial race – the most expensive in the state’s history at $212 million – Abbott outspent his Democratic opponent by almost $50 million. In 2018, he had 90 times more cash on hand than his Democratic opponent.

Texas’ lack of effective campaign finance regulations has given big donors access to power in the form of gubernatorial appointments.

An in-depth investigation by The Texas Tribune in 2022 revealed that 27 of the 41 members of the governor’s COVID-19 task force were campaign donors who had collectively paid $6 million toward the governor’s reelection. Many were business owners who had a vested interest in reopening the state.

Freedom of expression

Texas is also at the center of a national struggle over academic freedom, a key component of free expression.

Texas passed a law in 2023 requiring public universities to close their diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, offices, depriving the most vulnerable student communities of resources such as scholarships, mental health programs and career workshops.

The Texas Senate is considering expanding this legislation to prohibit “DEI curriculum and course content.”

The mere threat appears to be squelching freedom of thought and intellectual exploration in Texas universities already. The University of North Texas in November started editing course titles and syllabi to remove identity-based topics.

On Jan. 14, Abbott threatened to fire the president of Texas A&M University – a part of my university system – if faculty attended an academic conference showcasing the work of Black, Latino and Indigenous scholars.

Human rights at the border

Abbott’s campaign to control the U.S.-Mexico border has raised concerns among human rights groups about civil rights in the state.

In March of 2021, Abbott declared a state of emergency in counties on the Texas border, allowing him to deploy the Texas National Guard there. The initiative, Operation Lone Star, was supposed to stop migrants from crossing the border outside official government checkpoints.

Since border enforcement is a federal authority, however, the troops have mostly enforced state laws on trespassing or drugs and weapons possession. Guardsmen have also participated in busing migrants to Democratic-run cities such as New York and Chicago and built razor-wire barriers in the Rio Grande.

The result is an $11 billion policing program that has largely targeted Latino American citizens – not immigrants. Fully 96% of those arrested on trespassing charges are Latino, and 75% of those facing court proceedings for that and other crimes as a result of Operation Lone Star are U.S. citizens.

Michael Gonzalez/Getty Images

Women’s freedoms

Finally, women’s right to bodily autonomy is under threat in Texas, which has one of the country’s most restrictive abortion laws.

At least three women have died as a result of doctors being afraid to treat their miscarriages. Overall, maternal mortality rates have increased by 56% since the ban was imposed in 2021. Scary statistics haven’t stopped the state’s plans to tighten its ban.

The 2025 Texas legislative session began with Republican legislators having prefiled several bills aimed at ending abortion by mail services, including one that would reclassify common abortion pills as controlled substances like Valium or Ambien. Doctors warn that this reclassification could also make it harder for them to disperse these medications quickly in life-threatening emergencies.

And a handful of rural Texas counties have made it illegal to transport women seeking out-of-state abortions on their roads.

As Texas goes, so goes the nation?

The question of whether a government is democratic is often not black or white. It should be viewed on a sliding scale.

Freedom House, a nonpartisan international democracy watchdog, ranks countries on a 100-point scale based on the factors I mentioned earlier, among others, and labels countries as “free,” “partly-free” and “not free.”

The freest country in 2024, Finland, had a score of 100. The U.S. has been sliding down the rankings, receiving a score of 83 in 2024 – down from 94 in 2010. It’s still solidly in the “free” category, but U.S. democracy looks less like Germany’s and more like Romania’s. The antidemocratic policy changes made in Texas and a handful of other states contribute to this slide.

Freedom House doesn’t rank states, but if it did, Texas would likely still rate as a “free” democracy. There is space for dissent, opposition and free speech. Democratic politicians have occasional political victories.

But Texas is decidedly less democratic than the U.S. at large. Democracy here is not lost, but I fear Texas is in danger of becoming only “partly-free.”