For four months, the world’s richest man has played an unprecedented role in U.S. government. At the start of his 2025 term, President Donald Trump asked Elon Musk to cut government “waste and fraud.” That translated into the Musk-driven firing of 121,000 federal workers, essentially closing entire government programs and departments.

Many Americans protested Musk’s work. His unsupervised access to sensitive government materials and unchecked influence over the firing of federal employees represents an unprecedented moment in the United States. An unelected billionaire sought to overhaul the federal government, empowered and legitimized not by Congress but only by the president.

There are two individuals intrinsic to any presidential effort to restructure government: the president himself and the person he entrusts with the task.

In 2025, Musk has been the person designated to carry out the president’s aims.

In 1910, it was Frederick Cleveland, an academic, who was President William H. Taft’s designated head of his effort to streamline government.

Both presidents, Taft and Trump, have said they wanted to improve how government functioned.

But while Taft worked with Congress to launch his effort, Trump hasn’t followed that route. And the men each president asked to lead their efforts were vastly different in the responsibility given to them, and different in values as well as temperament.

Library of Congress

Power on Pennsylvania Avenue

Among the many historic attempts by presidents to streamline federal government, Taft’s administration provides a distinct parallel to an administration attempting to make government more efficient.

The Taft administration’s early 20th-century equivalent to the Musk-run Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, was called the Commission on Economy and Efficiency.

Unlike DOGE, created by presidential fiat via an executive order, Taft’s efficiency commission was funded by Congress.

Taft also delegated the work of this reorganization to trusted Cabinet subordinates, rather than an outsider who was not confirmed by Congress. Other presidents of Taft’s generation would have found it unthinkable to delegate such consequential work to someone outside of the bureaucracy to the extent that Trump has empowered Musk.

The work of Taft’s commission took place during a time of turmoil for the role and power of the president, as the country itself became more powerful and its governance more complex, calling for increased efficiency through streamlining.

Studying and streamlining government

Taft organized his commission in 1910, a year into his presidency. It lasted until his divided party led to his election defeat in 1912.

The commission’s aims were tied to economy and efficiency – as the commission itself was named. Indeed, Secretary of the Navy George von Lengerke Meyer, one of Taft’s trusted Cabinet members, concisely explained how the “main object was the establishment of a system which would enable the Secretary to administer his office efficiently and economically, with the advice of responsible expert advisers, ensuring continuity of policy for the future.”

Taft came to the presidency in 1909 with clear concepts of how the nation’s top office needed to become more powerful to meet the growing country’s burgeoning needs.

The presidency, he believed, also needed to expand its power to meet the modernizing demands of the Progressive Era in early 20th-century America. This era put new demands on government to be responsive to the country’s expanding needs, from grassroots demands by voters for greater government activism to professionals seeking more efficient support for their businesses from the government.

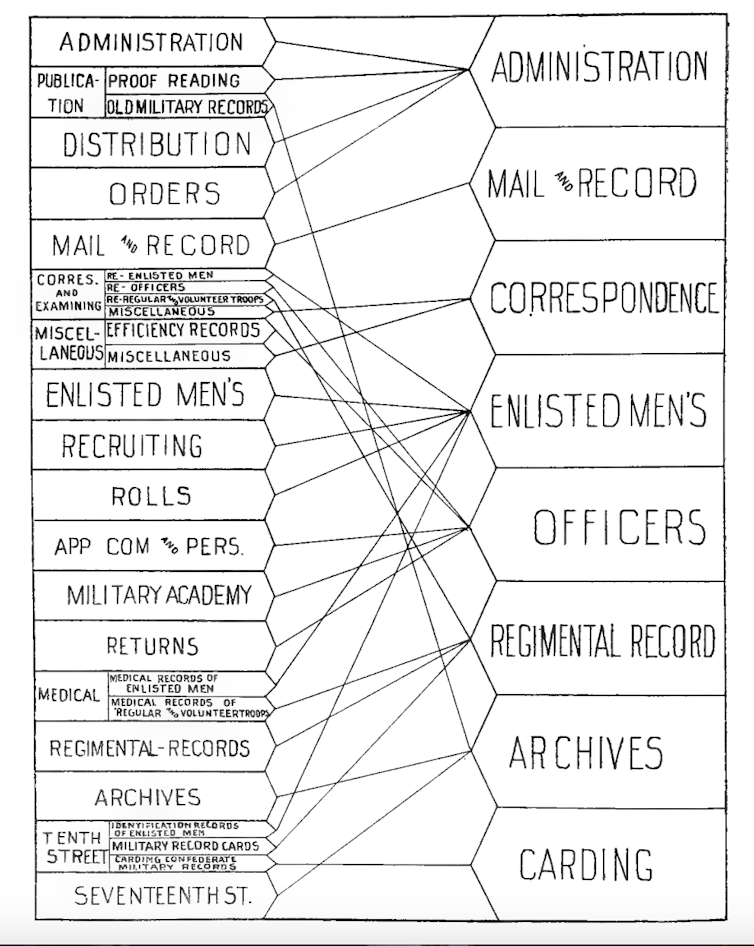

Taft was critically aware of existing inefficiency, with bureaucratic work overlapping at expense to the government, without any clear mandate, job description or hierarchy. The vision of the commission is clear in a diagram for the War Department that sought to streamline the bureaucracy, conglomerating the existing 18 divisions into eight.

archive.org

The Commission on Economy and Efficiency focused on providing solutions for this clearly defined problem of government inefficiency. At the time of Taft’s final message to Congress in 1913, the commission had submitted 85 reports to Taft encouraging the reorganization of executive departments, including new and specifically defined roles for government employees.

Google Books

Long-term, targeted changes

Unlike the radical unilateral actions taken by DOGE, the Taft commission recommended action to Congress for the long term, while making more targeted changes to the executive bureaucracy behind the scenes.

Despite Taft’s pleas stressing the need to sustain these changes beyond his tenure, Congress was tired of the empowerment of the executive by Republican presidents Theodore Roosevelt, followed by Taft, and had no incentive to support reorganization.

This is in direct contrast to Trump and Musk’s less substantiated concerns over “fraud and abuse” or ongoing vague concerns over the size and cost of the federal government. That phrasing may inspire more consensus over the problem, but not necessarily the solution.

Corbis Historical/Getty Images

Empowering the executive

Taft’s choice to head his commission, Frederick Cleveland, was a kindred spirit who believed in a strengthened presidency. Cleveland was an academic with past affiliations with the University of Pennsylvania and New York University. Congress accepted Cleveland’s nomination, seeing him as a pioneer in the realm of public administration.

Cleveland fit the Progressive Era’s mantra of employing experts. As a professional but not a member of the wealthy elite, and having been considered by Congress, Cleveland represents a clear distinction from Musk, who appears to have little understanding of what an average American may need from an operative federal bureaucracy.

Cleveland reflected the Taft administration’s approach of wanting to remold the government without animosity toward federal workers specifically or the government more broadly. He embraced the Progressive Era ethos in seeking to rectify inefficiency.

Streamlining did not equate to big cuts. The priority remained ensuring the American government could meet the increased demands of the new century.

Similar to DOGE, the White House was the command center for the Commission on Economy and Efficiency. That enabled Taft to manage reorganization of the executive branch from the Oval Office.

Not all of the modernizing and streamlining of the federal government would come at the behest of Taft’s commission.

Impatient to implement change while awaiting the commission’s reports, and with the commission hampered by a decrease in congressional funding in 1912, Taft had immediately sought improvement within his own administration.

But when the commission’s reports were finally available, Taft was in the unfortunate position of being a lame duck and could do little besides emphasize the need for further action.

While limited in the short term, the commission’s reports were later credited for major changes: “Although the report fell on deaf ears in Congress, it would become an essential roadmap for the budget reforms of 1921. The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 addressed and mirrored the concerns and proposals of the Commission’s Report,” as described by the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation.

Unlike DOGE, the approach of Taft and his commission focused on streamlining rather than gutting federal bureaucracy.

That approach was reflective of an era when experts were revered and sought after rather than maligned. As an experienced bureaucrat, Taft characteristically directed that the problem of government inefficiency be studied. This secured his legacy, as his agenda was eventually put into practice and embraced, proving his reflective approach to be ahead of its time.