Five years after the pandemic forced children into remote instruction, two-thirds of U.S. fourth graders still cannot read at grade level. Reading scores lag 2 percentage points below 2022 levels and 4 percentage points below 2019 levels.

This data from the 2024 report of National Assessment of Educational Progress, a state-based ranking sometimes called “America’s report card,” has concerned educators scrambling to boost reading skills.

Many school districts have adopted an evidence-based literacy curriculum called the “science of reading” that features phonics as a critical component.

Phonics strategies begin by teaching children to recognize letters and make their corresponding sounds. Then they advance to manipulating and blending first-letter sounds to read and write simple, consonant-vowel-consonant words – such as combining “b” or “c” with “-at” to make “bat” and “cat.” Eventually, students learn to merge more complex word families and to read them in short stories to improve fluency and comprehension.

Proponents of the curriculum celebrate its grounding in brain science, and the science of reading has been credited with helping Louisiana students outperform their pre-pandemic reading scores last year.

In practice, Louisiana used a variety of science of reading approaches beyond phonics. That’s because different students have different learning needs, for a variety of reasons.

Yet as a scholar of reading and language who has studied literacy in diverse student populations, I see many schools across the U.S. placing a heavy emphasis on the phonics components of the science of reading.

If schools want across-the-board gains in reading achievement, using one reading curriculum to teach every child isn’t the best way. Teachers need the flexibility and autonomy to use various, developmentally appropriate literacy strategies as needed.

Phonics fails some students

Phonics programs often require memorizing word families in word lists. This works well for some children: Research shows that “decoding” strategies such as phonics can support low-achieving readers and learners with dyslexia.

However, some students may struggle with explicit phonics instruction, particularly the growing population of neurodivergent learners with autism spectrum disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. These students learn and interact differently than their mainstream peers in school and in society. And they tend to have different strengths and challenges when it comes to word recognition, reading fluency and comprehension.

This was the case with my own child. He had been a proficient reader from an early age, but struggles emerged when his school adopted a phonics program to balance out its regular curriculum, a flexible literature-based curriculum called Daily 5 that prioritizes reading fluency and comprehension.

I worked with his first grade teacher to mitigate these challenges. But I realized that his real reading proficiency would likely not have been detected if the school had taught almost exclusively phonics-based reading lessons.

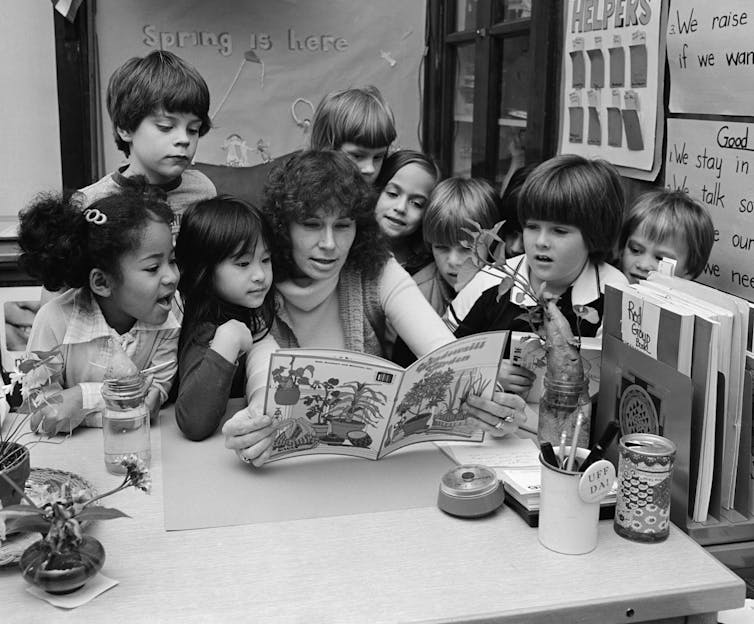

Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Another weakness of phonics, in my experience, is that it teaches reading in a way that is disconnected from authentic reading experiences. Phonics often directs children to identify short vowel sounds in word lists, rather than encounter them in colorful stories. Evidence shows that exposing children to fun, interesting literature promotes deep comprehension.

Balanced literacy

To support different learning styles, educators can teach reading in multiple ways. This is called balanced literacy, and for decades it was a mainstay in teacher preparation and in classrooms.

Balanced literacy prompts children to learn words encountered in authentic literature during guided, teacher-led read-alouds – versus learning how to decode words in word lists. Teachers use multiple strategies to promote reading acquisition, such as blending the letter sounds in words to support “decoding” while reading.

Another balanced literacy strategy that teachers can apply in phonics-based strategies while reading aloud is called “rhyming word recognition.” The rhyming word strategy is especially effective with stories whose rhymes contribute to the deeper meaning of the story, such as Marc Brown’s “Arthur in a Pickle.”

After reading, teachers may have learners arrange letter cards to form words, then tap the letter cards while saying and blending each sound to form the word. Similar phonics strategies include tracing and writing letters to form words that were encountered during reading.

There is no one right way to teach literacy in a developmentally appropriate, balanced literacy framework. There are as many ways as there are students.

What a truly balanced curriculum looks like

The push for the phonics-based component of the science of reading is a response to the discrediting of the Lucy Calkins Reading Project, a balanced literacy approach that uses what’s called “cueing” to teach young readers. Teachers “cue” students to recognize words with corresponding pictures and promote guessing unfamiliar words while reading based on context clues.

A 2024 class action lawsuit filed by Massachusetts families claimed that this faulty curriculum and another cueing-based approach called Fountas & Pinnell had failed readers for four decades, in part because they neglect scientifically backed phonics instruction.

But this allegation overlooks evidence that the Calkins curriculum worked for children who were taught basic reading skills at home. And a 2021 study in Georgia found modest student achievement gains of 2% in English Language Arts test scores among fourth graders taught with the Lucy Calkins method.

Nor is the method unscientific. Using picture cues with corresponding words is supported by the predictable language theory of literacy.

This approach is evident in Eric Carle’s popular children’s books. Stories such as the “Very Hungry Caterpillar” and “Brown Bear, Brown Bear What do you See?” have vibrant illustrations of animals and colors that correspond with the text. The pictures support children in learning whole words and repetitive phrases, suchg as, “But he was still hungry.”

H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images

The intention here is for learners to acquire words in the context of engaging literature. But critics of Calkins contend that “cueing” during reading is a guessing game. They say readers are not learning the fundamentals necessary to identify sounds and word families on their way to decoding entire words and sentences.

As a result, schools across the country are replacing traditional learn-to-read activities tied to balanced literacy approaches with the science of reading. Since its inception in 2013, the phonics-based curriculum has been adopted by 40 states and the Disctrict of Columbia.

Recommendations for parents, educators and policymakers

The most scientific way to teach reading, in my opinion, is by not applying the same rigid rules to every child. The best instruction meets students where they are, not where they should be.

Here are five evidence-based tips to promote reading for all readers that combine phonics, balanced literacy and other methods.

1. Maintain the home-school connection. When schools send kids home with developmentally appropriate books and strategies, it encourages parents to practice reading at home with their kids and develop their oral reading fluency. Ideally, reading materials include features that support a diversity of learning strategies, including text, pictures with corresponding words and predictable language.

2. Embrace all reading. Academic texts aren’t the only kind of reading parents and teachers should encourage. Children who see menus, magazines and other print materials at home also acquire new literacy skills.

3. Make phonics fun. Phonics instruction can teach kids to decode words, but the content is not particularly memorable. I encourage teachers to teach phonics on words that are embedded in stories and texts that children absolutely love.

4. Pick a series. High-quality children’s literature promotes early literacy achievement. Texts that become increasingly more complex as readers advance, such as the “Arthur” step-into-reading series, are especially helpful in developing reading comprehension. As readers progress through more complex picture books, caregivers and teachers should read aloud the “Arthur” novels until children can read them independently. Additional popular series that grow with readers include “Otis,” “Olivia,” “Fancy Nancy” and “Berenstain Bears.”

5. Tutoring works. Some readers will struggle despite teachers’ and parents’ best efforts. In these cases, intensive, high-impact tutoring can help. Sending students to one session a week of at least 30 minutes is well documented to help readers who’ve fallen behind catch up to their peers. Many nonprofit organizations, community centers and colleges offer high-impact tutoring.