There are a few reasons why embryos aren’t making it into research labs, says Hartshorne. Part of the problem is that most IVF cycles happen at clinics that don’t have links with academic research centers.

As things stand, embryos tend to be stored at the clinics where they were created. It can be difficult to get them to research centers—clinic staff don’t have the time, energy, or head space to manage the paperwork legally required to get embryos donated to specific research projects, said Hartshorne. It would make more sense to have some large, central embryo bank where people could send embryos to donate for research, she added.

A particular problem is the paperwork. While the UK is rightly praised for its rigorous approach to regulation of reproductive technologies, which embryologists around the globe tend to describe as “world-leading,” there are onerous levels of bureaucracy to contend with, said Hartshorne. “When patients contact me and say ‘I’d like to give my embryos or my eggs to your research project,’ I usually have to turn them away, because it would take me a year to get through the paperwork necessary,” she said.

Perhaps there’s a balance to be struck. Research on embryos has the potential to be hugely valuable. As the film Joy reminds us, it can transform medical practice and change lives.

“Without research, there would be no progress, and there would be no change,” Hartshorne said. “That is definitely not something that I think we should aspire to for IVF and reproductive science.”

Now read the rest of The Checkup

Read more from MIT Technology Review‘s archive

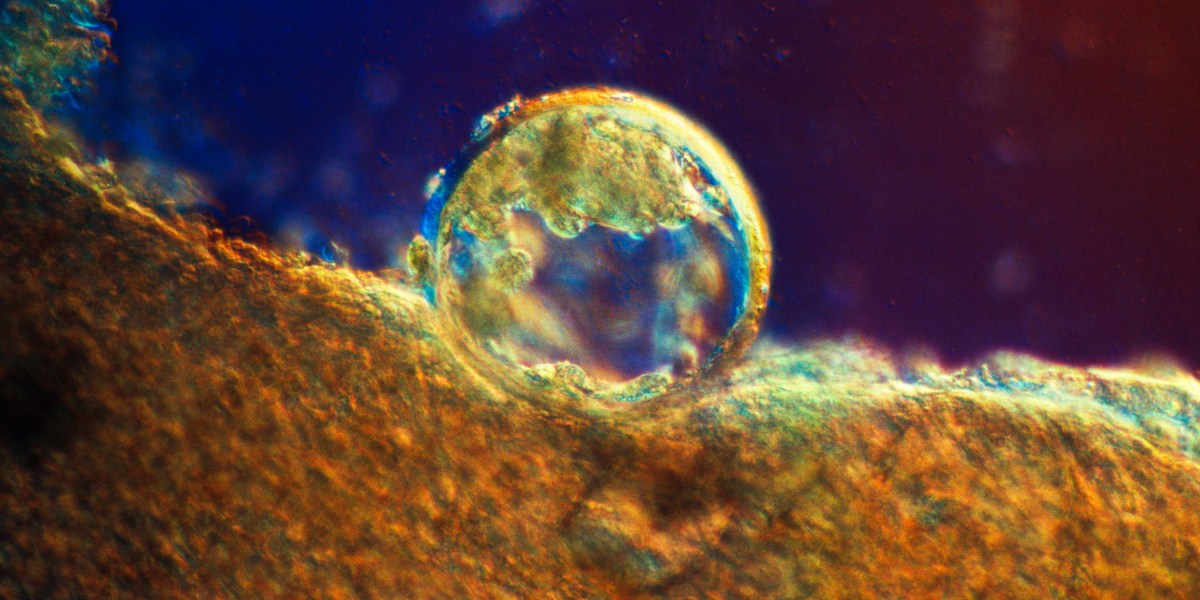

Scientists are working on ways to create embryos from stem cells, without the use of eggs or sperm. How far should we allow these embryo-like structures to develop?

Researchers have implanted these “synthetic embryos” in monkeys. So far, they’ve been able to generate a short-lived pregnancy-like response … but no fetuses.

Others are trying to get cows pregnant with synthetic embryos. Reproductive biologist Carl Jiang’s first goal is to achieve a cow pregnancy that lasts 30 days.