THIRTEEN people have died in a major outbreak of a highly contagious “eye-bleeding disease” – as cases almost doubled in the space of a week.

The condition – which has a mortality rate of up to 90 per cent – has sickened 58 people as it spreads rapidly through the East African nation of Rwanda.

3

3

3

An outbreak of the bug, which is a close cousin to Ebola, was first confirmed in Rwanda at the end of last month.

As of September 30, at least 26 Marburg virus infections had been reported in the East African country.

In an update issued on October 8, Rwanda’s ministry of health warned cases had almost doubled in the space of a few days.

A total of 58 people have been sickened by the virus and 13 have died.

Meanwhile, 33 patients remain in isolation and 12 have recovered.

Health authorities have completed a whopping 2,655 tests to detect people carrying the highly infectious disease.

This is the first documented outbreak of Marburg virus – which causes uncontrolled bleeding from different body parts, including the eyes – in Rwanda, and authorities are racing to trace its source.

Health officials are also rolling out hundreds of doses of an experimental vaccine in a bid to stop the fatal virus in its tracks.

Those most at risk – like doctors and people who’ve come into contact with Marburg patients – will be the first to receive the jabs, Health Minister Sabin Nsanzimana said.

It comes after the detection of two suspected Marburg infections shut down a major train station in Hamburg, Germany.

Passengers were evacuated from two platforms at Hamburg Central Station as emergency personnel, dressed in full protective gear, boarded a train arriving from Frankfurt.

Fears of the disease spreading into Europe were further sparked by reports of a person suspected of carrying the disease travelling into Belgium.

But the Belgian government health authority told The Sun that the individual feared to have potentially carried Marburg virus was immediately put into isolation and has now completed the full incubation period without developing any symptoms.

The bug was first identified in 1967 in Marburg, Germany.

It’s a “cousin” to the deadly Ebola virus, which killed more than 11,000 people during an outbreak in West Africa between 2014 and 2016.

Virologist Adam Hume, of Boston University in Massachusetts, told the journal Nature that the death rate from Marburg has ranged from 23 per cent to 90 per cent in past outbreaks.

While there are no vaccines or treatments, supportive care can increase a person’s chances of survival.

What is Marburg virus?

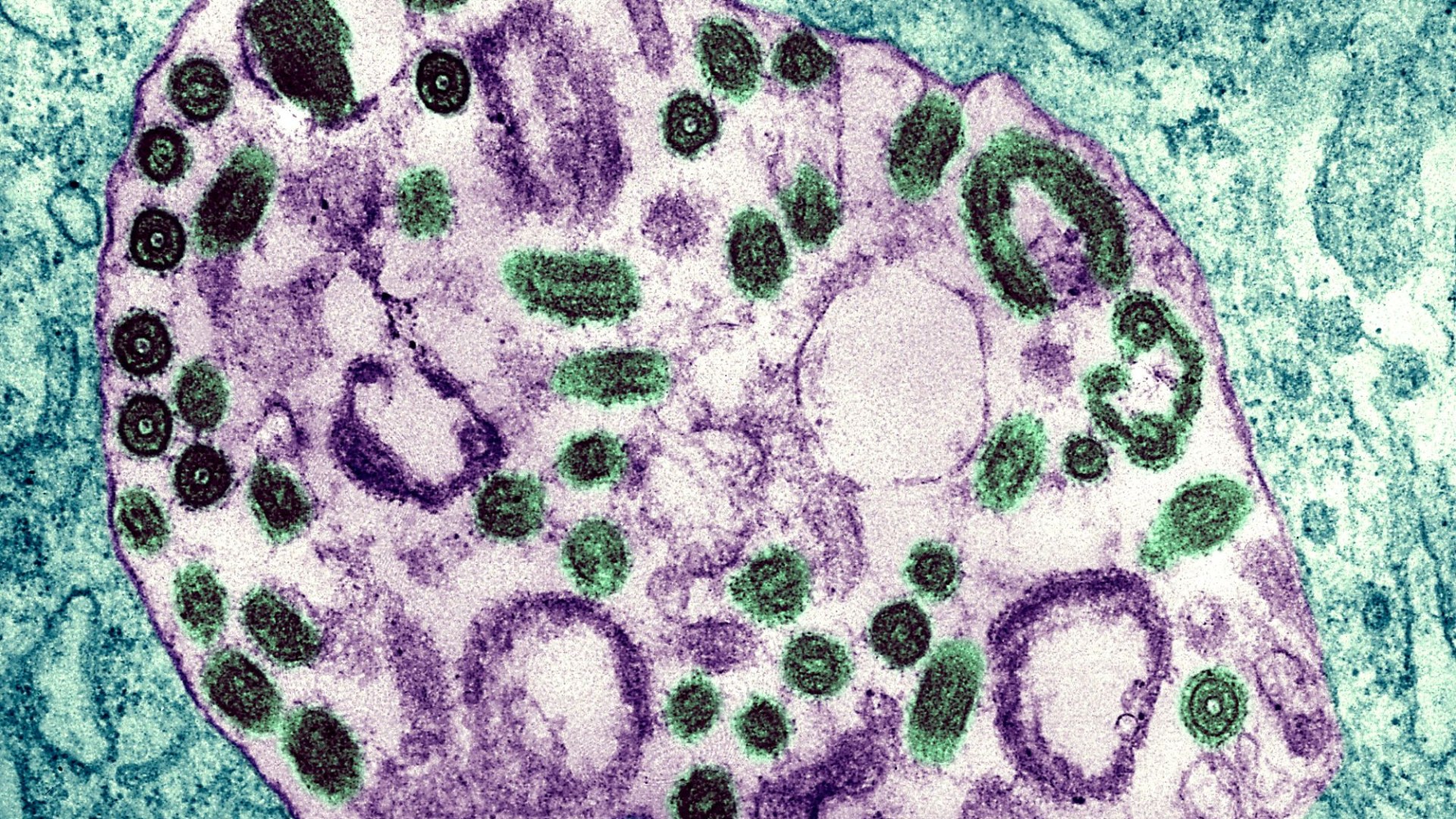

Marburg is a filovirus like its more famous cousin, Ebola.

These are part of a broader group of viruses that can cause viral haemorrhagic fever, a syndrome of fever and bleeding.

Up to 90 per cent of those infected die.

The first outbreaks occurred in 1967 in lab workers in Germany and Yugoslavia who were working with African green monkeys imported from Uganda.

The virus was identified in a lab in Marburg, Germany.

Since then, outbreaks have occurred in a handful of countries in Africa, less frequently than Ebola.

Marburg’s natural host is a fruit bat, but it can also infect primates, pigs and other animals.

Human outbreaks start after a person has contact with an infected animal.

It’s spread between people mainly through direct contact, especially with bodily fluids, and it causes an illness like Ebola, with fever, headache and malaise, followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, and aches and pains.

The bleeding follows about five days later, and it can be fatal in up to 90 per cent of people infected.

Early symptoms caused by the virus can be similar to those of other diseases, including high fever, headache and malaise.

But people with Marburg soon develop severe watery diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting.

Patients may also begin bleeding from their noses, gums or other areas of their body, including the eyes.

Marburg jumps to humans from fruit bats.

It’s then spread from person to person through very close contact with the blood, bodily fluids or secretions from an infected patient, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) notes.

This can be from direct contact or from touching a surface that’s got blood or bodily fluids on it.

EFFORTS TO CONTAIN VIRUS

In Rwanda, some of the first people later found to be infected with Marburg initially tested positive for malaria.

But healthcare workers knew something wasn’t right when the usual treatment wasn’t working.

By the time the workers realised they had a Marburg outbreak on their hands, a number of them had already become infected, Mr Nsanzimana said in a press conference last week.

Rwanda this week began trialling an experimental vaccine in the hopes of containing the virus.

The east African country has received 700 doses of the vaccine from the Sabin Vaccine Institute, a US-based non-profit organisation.

The Marburg jab has only been tested in adults aged 18 and older, with no current plans to conduct trials in children.

According to the BBC, Rwanda’s health minister said there were plans to order more doses of the jab.

Most of the recorded Marburg cases so far have involved healthcare staff treating infected patients in and around Kigali, the country’s capital.

Kigali is home to 1.2million people and has a well-connected airport, raising fears of international spread.

FEARS OF GLOBAL SPREAD

Paul Hunter, a professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia, told The Sun this outbreak of Marburg could “crop up in any country globally”.

“The incubation period is between five and 15 days, plenty long enough for someone to get on a plane and fly anywhere in the world,” he explained.

The incubation period of a virus is the time between exposure to the virus and the onset of symptoms.

“Airport screening wouldn’t eliminate that risk due to the long incubation period,” Prof Paul said, as people could be travelling without showing any symptoms.

Should we be worried?

By Professor Paul Hunter, from the University of East Anglia

Even if the Marburg was brought over to Europe or the UK, the chance of it spreading like wildfire is small.

The disease spreads easily in hospitals in Africa because they don’t have the infection prevention resources we have in the West.

Once a diagnosis has been made in the UK the patient would be transferred to one of the High Level Isolation Units either at the Royal Free, London or Newcastle.

Once there the staff are very well trained in how to protect themselves.

The risk to healthcare workers would likely be early in the illness when, fortunately, patients are not as infectious.