In Texas, where I live, marijuana has long been illegal. Yet on a busy street in my Houston neighborhood, at least five stores within a half-mile of each other sell cannabis products that promise a strong high.

Texas isn’t alone. Due to a mix of recent legal changes and an uncertain policy landscape, residents in roughly half of American states have easy access to impairing hemp products that bear a strong resemblance to marijuana and are far less regulated.

As hemp sales soar – reaching nearly US$3 billion in 2023 – a number of states are tightening their restrictions, while experts are analyzing the public health implications. That’s why I analyzed hemp policies in all 50 states with some of my colleagues at Rice University’s Baker Institute, where I’m a drug policy fellow.

Marijuana and hemp: Same plant, different policies

Marijuana and hemp are both varieties of cannabis sativa, a plant with many uses that produces thousands of compounds. Among them is the popular intoxicant delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol, or delta-9 THC.

Hemp is widely valued as an industrial crop, and for most of American history, farmers freely cultivated it. But by the mid-20th century, lawmakers had grown increasingly opposed to marijuana and were concerned by hemp’s similarity to its impairment-causing cousin.

In an effort to permit hemp cultivation while prohibiting production of a psychoactive plant, the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 defined hemp as all parts of the cannabis plant with less than 0.3 percent concentration of delta-9 THC by dry weight. Cannabis that exceeded this threshold was considered marijuana.

The 1970 Controlled Substances Act ushered in the modern era of prohibition of marijuana and other drugs. Hemp remained technically legal, but because of its similarity to marijuana, it was listed as a Schedule I drug, alongside heroin and other substances deemed to have a high potential for abuse and no medical value.

Because of hemp’s Schedule I status, the Drug Enforcement Administration tightly regulated its production. But hemp farmers have long argued that these regulations were excessive – and in 2018, Congress agreed. That year, lawmakers passed a farm bill that removed hemp from the Controlled Substances Act and legalized the manufacture and sale of hemp and its derivatives.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dz6a5HmTdw

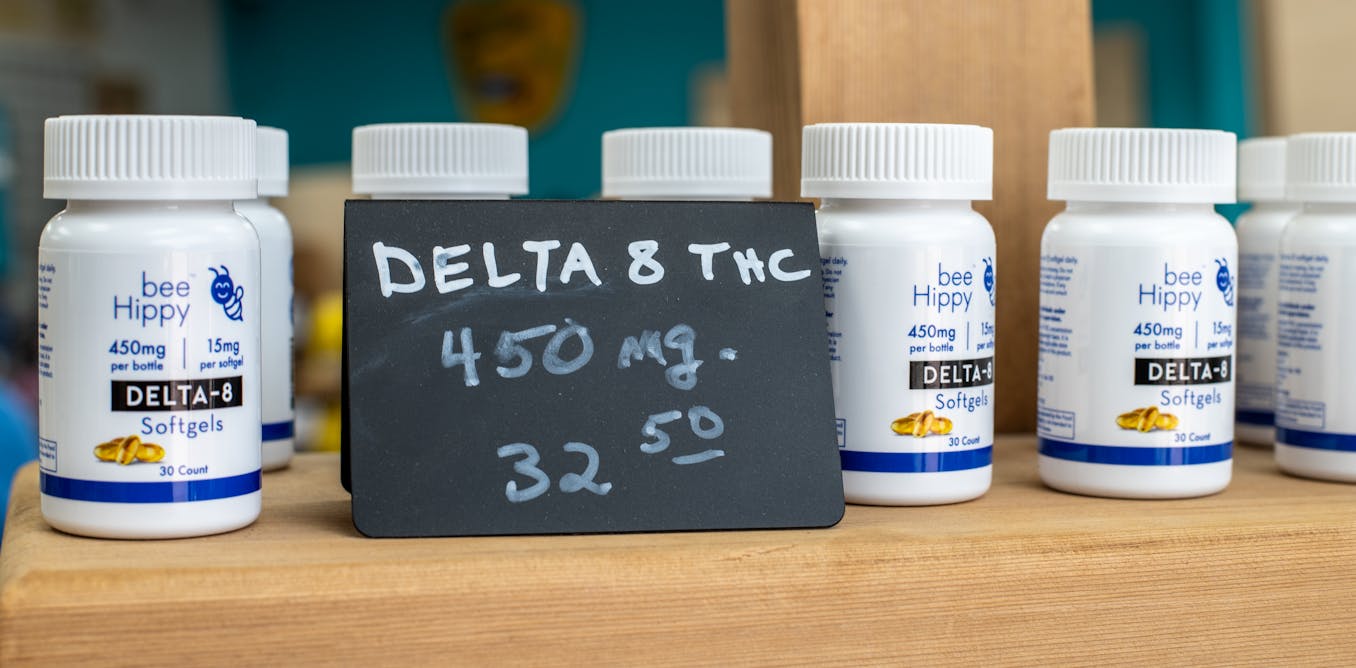

Crucially, the 2018 bill still defines hemp as all parts of the plant and its derivatives that have less than 0.3 percent delta-9 THC. But it left a loophole: While delta-9 is the most well-known form of THC, it’s not the only one. Other forms of THC, known as THC isomers, have similar effects. These isomers, like delta-8 and delta-10 THC, can be derived from the hemp plant, and like delta-9 THC, they can cause impairment. The 2018 Farm Bill legalized all of them.

In 2023, sales of hemp-derived cannabinoids reached US$2.8 billion. Market growth has been accompanied by a rise in adverse health events. Chemists have expressed alarm at how some hemp products are made, and analyses of commercially available products have found them to contain heavy metals, residual solvents and pesticides.

Given the lax regulatory environment, many public officials now question the lack of guardrails on this burgeoning hemp industry. As a result, officials and governments across the country are now enacting or considering policy changes.

Some states are imposing age and advertising restrictions

In 2023, 11.4% of 12th graders said they had used hemp-derived delta-8 THC in the past year. Easy access to any substance can encourage use, and THC can have negative impacts on the adolescent brain.

While federal law prohibits the sale of tobacco and alcohol to individuals under 21, there is no similar national requirement for hemp. But at least 27 states that permit the sale of hemp-derived products now have minimum age requirements, and several others have pending legislation.

Lessons from the tobacco market also demonstrate that advertising restrictions can reduce the use of legal but potentially harmful products. Most efforts to curtail hemp advertising focus on youth. Sixteen states restrict the use of packaging and marketing materials that may appeal to minors. Meanwhile, federal regulations also limit youth-targeted marketing.

There are fewer restrictions on advertising to adults. The Food and Drug Administration does prohibit using unverified health claims to sell hemp products, but this standard gives the industry plenty of leeway. Hemp ads often tout their purported physical benefits, like reducing pain or improving sleep, or portray them as mood-boosters that can make one feel euphoric and aroused, with few downsides.

Other states are establishing potency limits

The use of products high in THC has been linked to greater risk of cannabis dependence and adverse mental health outcomes. Concerns about product potency have led all states with recreational marijuana markets to limit the amount of delta-9 THC in edible products. This threshold is typically around 10 milligrams, a dose that’s strong enough to affect most people.

Hemp is a different story. To satisfy federal requirements, hemp just has to have less than 0.3% delta-9 THC by weight. This limit sounds low, but the weight-based metric does not account for heavier products, like food and drinks.

For example, a 50-gram candy bar – roughly the size of a Snickers bar – with 150 milligrams of hemp-derived delta-9 THC is legal in the 34 states that don’t have milligram caps on hemp products. This is a dose 15 times higher than what any recreational marijuana market allows. Meanwhile, states that only restrict hemp’s delta-9 content also leave the door open to products with high amounts of other forms of THC.

At least 13 states have responded to potency concerns by adding milligram caps on the total THC permitted in a single serving of a hemp product. Some of these limits are so low – 1 milligram or less in Connecticut, New York, Montana and Rhode Island – that one serving is unlikely to cause impairment.

Enforcement is a wild card

Only regulations that are enforced are effective, and states differ in the level of energy they devote to industry oversight.

In Virginia, the Office of Hemp Enforcement has issued over $12 million in fines to noncompliant hemp retailers since its creation in 2023. On the other end of the spectrum, Massachusetts considers hemp-derived THC products illegal, but it has not provided local jurisdictions with funding for enforcement, resulting in continued availability of prohibited products.

Some states with legal hemp markets have added additional sales taxes to help fund enforcement. In Nebraska, Missouri and Connecticut, attorneys general have sued hemp retailers for selling illegal items, marketing to minors and engaging in deceptive trade practices.

As the hemp industry expands, so will concerns about how to protect public health. The demand for THC, and the market to supply it, continues to grow. If lawmakers want to develop industrywide safety standards or deal with the challenges of online marketplaces that sell hemp products to minors, it will take action from Washington. In the meantime, many states and policymakers are exploring an expansive middle ground between unfettered access and blanket bans.