Former presidents don’t criticize their successors in public.

Or do they?

Former Presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Joe Biden have all criticized President Donald Trump in recent months.

In April 2025, Obama, for example, spoke about the importance of preserving the international order, meaning the system of rules, norms and institutions that have been active since World War II. He said: “And this is an important moment, because in the last two months, we have seen a U.S. government actively try to destroy that order and discredit it. And the thinking, I gather, is that somehow, since we are the strongest, we’re going to be better off if we can just bully people into doing whatever we want.”

Biden also offered his own negative comments on April 15: “In fewer than 100 days, this new administration has done so much damage,” he said in his first public remarks since leaving office.

Some commentators have called these former presidents’ remarks “unprecedented.”

Many Americans are accustomed to former presidents not speaking about – let alone criticizing – the current president.

As a scholar of the presidency, I know that most presidents stay quiet about their successors, regardless of what the current president does or says. They do this to avoid undermining both their own reputations as well as the stability of the presidency itself.

But I am also struck by the fact that this tradition is not as entrenched as former presidents might claim or as many Americans believe.

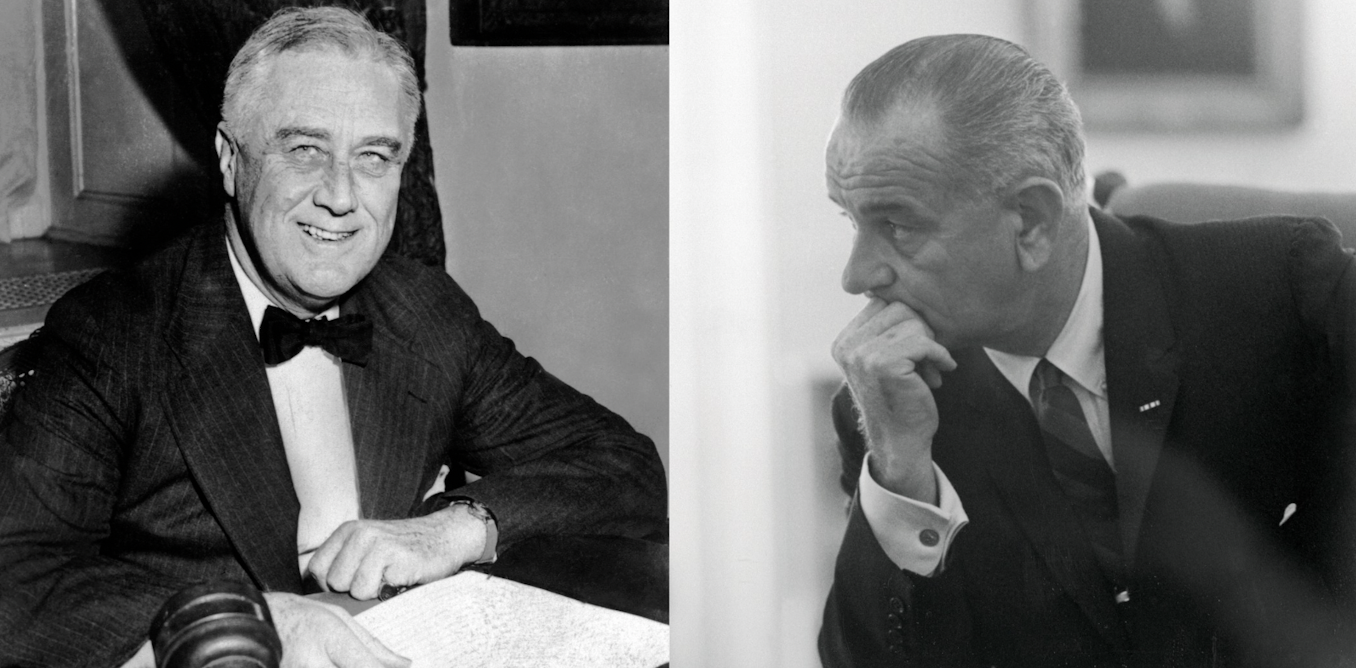

Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images

Presidents who bucked the norm

President George Washington established the precedent that presidents retire after two terms and steer clear of public statement. John Quincy Adams, the sixth U.S. president, established a different model.

After Adams lost his bid for reelection in 1828 to Andrew Jackson, he served in the House of Representatives from 1831 through 1848. Congress is an unusual perch for a former president, but it’s a place where criticizing sitting presidents and their policies is part of the job. Adams had plenty of criticism there for his successors, including Jackson and James K. Polk.

Nearly half a century later, President Teddy Roosevelt was disappointed that his hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft, failed to live up to Roosevelt’s vision of reform. Roosevelt went from criticizing Taft privately in political circles to campaigning against him publicly in 1912, aiming to win a nonconsecutive second term. Democrat Woodrow Wilson eventually won that election, beating out Taft and Roosevelt.

Richard Nixon, who, in 1974, became the only president to resign from office, wrote a series of books in the 1980s and 1990s that sought to redeem his own sullied image by casting himself as a visionary statesman. Nixon’s books also included plenty of unsolicited advice – and implicit criticism – for Democratic and Republican presidents alike.

Before becoming the beloved elder statesman of the former presidents club in 1980, Jimmy Carter earned the ire of his successors for his outspokenness. He said that President Ronald Reagan’s administration was an “aberration on the political scene” and said that one of Clinton’s political pardons was “disgraceful.”

With the exception of Roosevelt, these former presidents who criticized their successors all felt they had something to prove. Anxious to redeem their legacies, they did not retire quietly.

A healthy foray into retirement

So why don’t we all know these stories, and instead believe that past presidents simply keep their mouths shut?

Americans have long treated presidential retirement as a symbol of a healthy democracy. And that story of retirement emphasizes how former presidents often leave politics behind them.

The trajectory of presidents finding peace and contentment in retirement, surrounded by friends and family, is an appealing way for presidential biographers to end a story. These stories have included narratives about Harry Truman taking a cross-country road trip only months after leaving the White House in 1953, and George W. Bush taking up painting.

In reality, former presidents have led complex lives of happiness and loss, withdrawal and engagement. The energy and ambition that brought them to the White House often make retirement difficult. And, over the long history of the presidency, former presidents have become increasingly public figures.

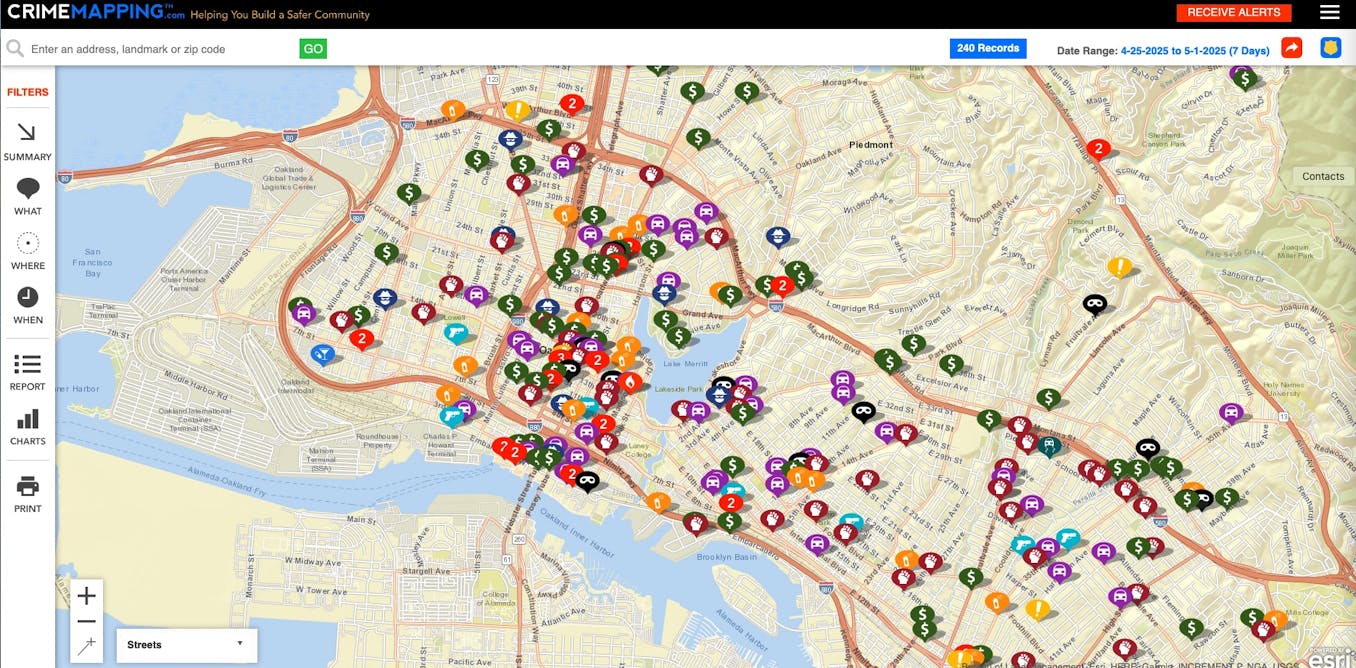

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

A shifting role

Another important factor in the growing prominence of former presidents is how their roles have recently changed.

Beginning in the 1990s, former presidents and first ladies tried to publicly show friendship and agreement with their counterparts.

George H.W. Bush and Clinton, for example, teamed up to raise money for disaster relief after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami in South and Southeast Asia. In 2017, Bush’s son George W. Bush, himself a former president by that time, called Clinton his “brother with a different mother.”

Former first lady Michelle Obama and Barack Obama have publicly thanked George W. Bush and Laura Bush for helping their family adjust to life in the White House. Michelle Obama has also become known for her personal friendship with George W. Bush.

And as medical advances enabled former presidents to live longer than ever, the relationships within a growing former presidents club became the subject of books, movies and television segments.

All of these stories had the same message – that all presidents are committed to their country. Likewise, the amiable relationship between former and sitting presidents shows that if party leaders could overcome partisanship in the name of unity and friendship, so too could other Americans.

In a remarkable moment, for example, three presidents from two different parties – Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama – came together for a video before Biden’s 2021 inauguration to call for unity in a moment of crisis.

Following the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol attack, they used their connection as presidents to tell a national story. As Bush said, “Well, I think the fact that the three of us are standing here talking about a peaceful transfer of power speaks to the institutional integrity of our country.”

“America’s a generous country, people of great hearts. All three of us were lucky to be the president of this country,” Bush continued.

The Republican former president looked at the Democrats on either side of him and smiled.

A new kind of presidential relations

While friendships between presidents became more common in the 1990s and 2000s, Clinton and especially Trump were doing something different by the 2016 election.

In 2016, Clinton became an active partisan in support of his wife, Hillary Clinton, during her unsuccessful bid for president.

Both Clintons remained public critics of Trump long after he assumed office in 2017.

For his part, Trump as a politician and then president immediately dismissed the notion of friendship with his predecessors and former competitors. He was quick to condemn Hillary Clinton – and especially Obama – in the early years of his first presidency.

No sooner did Trump lose the 2020 election than he was heaping public scorn on Biden with an energy that only increased after Trump entered the 2024 race.

Trump’s criticism of Biden did not stop after his 2024 victory, with the White House issuing statements like a pledge “to turn back the economic plague unleashed by the Biden Administration.”

Trump has escalated attacks on other presidents. But he was not the first to criticize his successors or predecessors.