If Donald Trump has taught Americans anything, it’s that political parties can shift positions on any number of issues and retain strong support. Republicans had once been aggressive Cold Warriors, standing shoulder to shoulder with allies against Russia, but now they are isolationists. They once favored so-called “free markets,” but now they support tariffs. And they once supported cutting budget deficits, but now they balloon those deficits with tax cuts.

Same party, different policies.

This accords with recent scholarship showing that American political parties don’t have much ideological coherence around concepts such as “freedom” or “equality” but instead are more like social groups with strong communal bonds such as common sympathies and common enemies.

It turns out that political parties are mostly just people rooting for their side, the way you might support a sports team. It doesn’t matter whether your team changes tactics. You still root for them.

People do switch allegiances, but it often takes a traumatic event to stop seeing fellow partisans as good, reasonable people.

Republicans right now have strong tribal belonging that begins and ends with a single question: Do you support President Trump? They have a banner to march under: MAGA. And a song: “God Bless the U.S.A.” They live, laugh and love to own the libs. Their signs and symbols are simple and amusing. And they are effective.

The Democrats have nothing. No leader, no banner to march under, no signs and no symbols.

They used to.

New York Times archive

The liberal past

In the past, Democrats had a word to describe their sensibility: “liberal.” But now: RIP, liberal. No one, it seems, wants to be a liberal anymore.

In my research on uses and abuses of the word liberal, I discovered that liberalism is a relatively new word in American politics, really starting only in 1932.

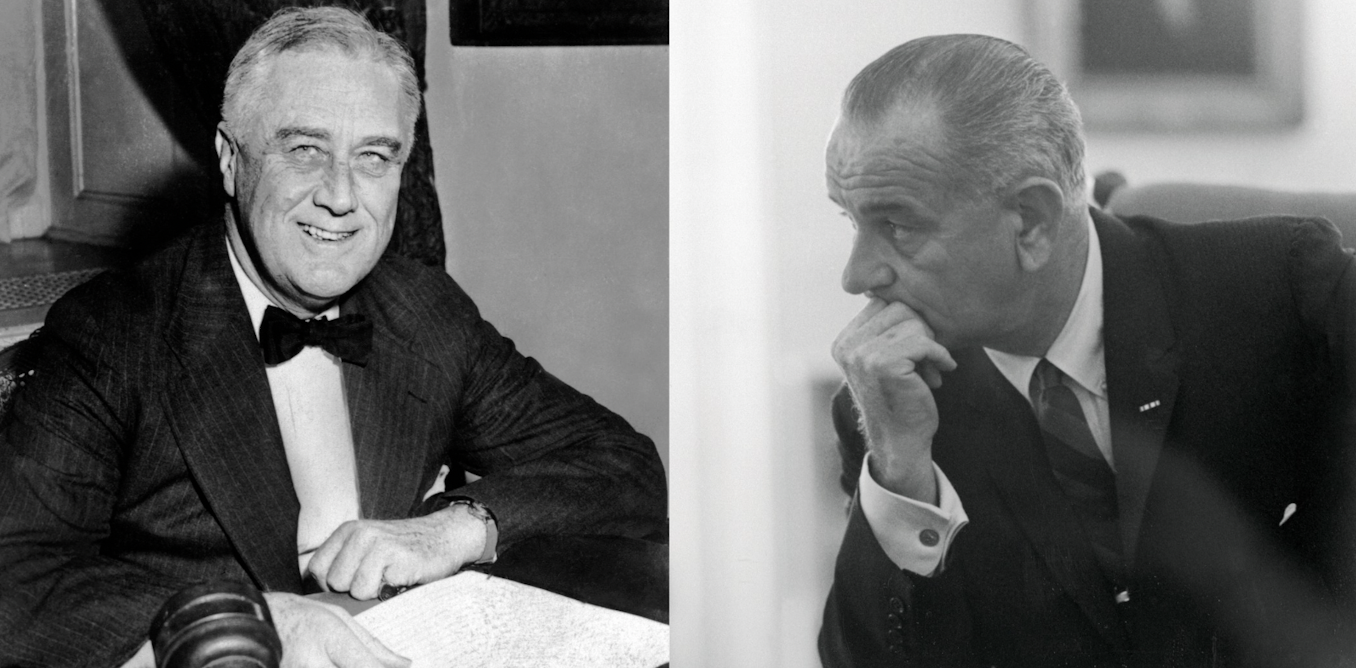

That year, presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt was searching for a way to fend off Republican accusations that his New Deal was “socialism,” a word with radical connotations.

Liberalism as a word predates FDR’s usage, but he redefined it to signify the government regulation of capitalism and the use of the state to provide citizens with basic economic security.

When in 1932 FDR accepted the nomination for president, he declared the Democratic Party “the bearer of liberalism,” by which he meant undertaking “planned action” while fighting for “the greatest good to the greatest number of our citizens.”

FDR pitted his liberalism against his opponents, whom he labeled “conservatives.” The U.S. has had the liberal-conservative divide ever since.

FDR’s successor, Democrat Harry Truman, recognized the power of the term, extravagantly claiming, “The liberal faith is the political faith of the great majority of Americans.”

President John F. Kennedy gloried in the word, too, defining a liberal as “someone who welcomes new ideas without rigid reactions, someone who cares about the welfare of the people.”

In 1960, philosopher Charles Frankel argued that liberalism as defined by FDR was a banner under which every Democrat marched, concluding that “anyone who today identifies himself as an unmitigated opponent of liberalism … cannot aspire to influence on the national political scene.”

Shifting meanings

Not for long.

For one thing, in the 1950s the word shifted meaning to better accord with the times, as it had done several times in the past. During the post-World War II economic expansion, “a large part of the New Deal public,” historian Richard Hofstadter wrote in 1954, “have become home-owners, suburbanites and solid citizens.”

Liberals therefore shifted liberalism. No longer were liberals solely about providing jobs and Social Security. They also demanded increased access to higher education, medical care and civil rights, and the elevation of popular culture.

In 1956, future presidential adviser Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called this shift one from “quantitative” to “qualitative liberalism.”

President Lyndon Johnson put this into effect in the mid-1960s. Johnson developed anti-poverty programs such as Head Start, but he also created cultural programs such as PBS, expanded civil rights and passed Medicare and Medicaid.

“We are a great and liberal and progressive democracy,” Johnson declared in 1966.

But Johnson’s qualitative liberalism came with costs. The programs expanded the federal bureaucracy, which by the late 1960s became noted for being ineffective and overly regulatory.

Civil rights laws were perceived as threatening to the white working class. And Johnson’s liberalism became wedded to the war in Vietnam, where by 1969 more than 500,000 Americans were fighting to protect liberalism from the supposedly creeping arms of communism.

Soon, the knives were out for liberals.

3 lines of attack

First, right-wing thinkers had already begun to portray liberals as little more than quasi-communists pushing for civil rights beyond most Americans’ desires.

In 1955, conservative impresario William F. Buckley Jr. founded the magazine National Review to create “a responsible dissent from the Liberal orthodoxy.” He titled his 1959 book “Up from Liberalism” and spent 217 of the book’s 229 pages attacking liberals.

Then leftist thinkers took their shot, imagining liberals as little more than beards for capitalism and foreign policy hawks.

Left-wing novelist Norman Mailer summed up this sentiment in 1962, writing, “I don’t care if people call me a radical, a rebel, a red, a revolutionary, an outsider, an outlaw, a Bolshevik, an anarchist, a nihilist or even a left conservative, but please don’t ever call me a liberal.”

Fred Stein Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Civil rights advocates took their turn, seeing liberals as halfway friends, unwilling to fully embrace equality. Historian Lerone Bennett Jr. wished liberals “a fond farewell” in 1964. In that same year, writer James Baldwin called white liberals an “affliction.”

With attacks coming from multiple sides, by the 1970s Democrats ran from the label. And without defenders, enemies redefined liberals, first as out-of-touch elitists, then as allies of corporations ignoring the demands of working people, and eventually, today, as woke snowflakes.

In 2009, political scientists examining a hundred years of polling data found that, starting in the mid-1960s, decreasing numbers of Americans referred to themselves as liberal. And because partisanship is a social dynamic, when the club began to shrink, the researchers wrote, it turned into “a spiral in which ‘liberal’ not only is unpopular, but becomes ever more so.”

The researchers also found that most Americans still supported “‘liberal’ public policies” such as “redistribution, intervention in the economy, and aggressive governmental action to solve social problems.” Americans, apparently, just hated the label.

“Owning the libs” has been the glue keeping together the Republican Party ever since.

From ‘abundance’ to ‘Waymo’

Democrats are now searching for a new label. What can replace liberalism?

New York Times columnist Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, who writes for The Atlantic, have proposed “abundance liberalism.” Other New York Times writers have also been busy envisioning this future. Reporter and editor David Leonhardt suggested “democratic capitalism.” Columnist Thomas Friedman improbably went with “Waymo Democrat,” referring to self-driving Waymo cars as a placeholder for an embrace of technological innovation.

More realistically, political analyst E.J. Dionne and historian James Kloppenberg are writing a history of “social democracy” as a potential rallying cry for Democrats, pointing to its use by the most popular politician in America, Bernie Sanders.

Whatever emerges, it’s helpful to remember that before 1932, hardly anyone in the U.S. used the word “liberal” to describe any kind of politics. Now, without finding a new emblem to rally behind, Democrats may be doing little more than battling that other neologism: MAGA.