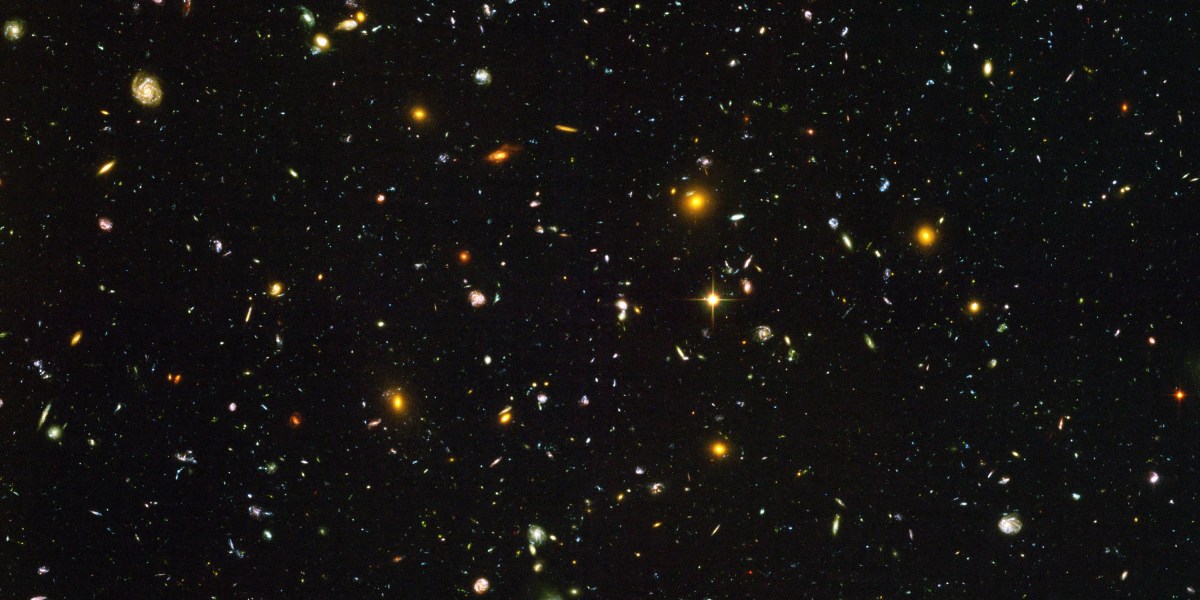

Other observatories, like the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, have already begun stitching together this map from their images of galaxies. But Rubin plans to do so with exceptional precision and scale, analyzing the shapes of billions of galaxies rather than the hundreds of millions that current telescopes observe, according to Andrés Alejandro Plazas Malagón, Rubin operations scientist at SLAC National Laboratory. “We’re going to have the widest galaxy survey so far,” Plazas Malagón says.

Capturing the cosmos in such high definition requires Rubin’s 3.2-billion-pixel Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST). The LSST boasts the largest focal plane ever built for astronomy, granting it access to large patches of the sky.

The telescope is also designed to reorient its gaze every 34 seconds, meaning astronomers will be able to scan the entire sky every three nights. The LSST will revisit each galaxy about 800 times throughout its tenure, says Steven Ritz, a Rubin project scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The repeat exposures will let Rubin team members more precisely measure how the galaxies are distorted, refining their map of dark matter’s web. “We’re going to see these galaxies deeply and frequently,” Ritz says. “That’s the power of Rubin: the sheer grasp of being able to see the universe in detail and on repeat.”

The ultimate goal is to overlay this map on different models of dark matter and examine the results. The leading idea, the cold dark matter model, suggests that dark matter moves slowly compared to the speed of light and interacts with ordinary matter only through gravity. Other models suggest different behavior. Each comes with its own picture of how dark matter should clump in halos surrounding galaxies. By plotting its chart of dark matter against what those models predict, Rubin might exclude some theories and favor others.

A cosmic tug of war

If dark matter lies on one side of a magnet, pulling matter together, then you’ll flip it over to find dark energy, pushing it apart. “You can think of it as a cosmic tug of war,” Plazas Malagón says.

Dark energy was discovered in the late 1990s, when astronomers found that the universe was not only expanding, but doing so at an accelerating rate, with galaxies moving away from one another at higher and higher speeds.