Macy’s announced on Jan. 9, 2025, that it will close its store in Center City Philadelphia in March. Immediately, residents and news outlets across the region asked: What will happen to the 120-year-old Wanamaker organ and annual Christmas light show?

As a historian of Philadelphia and historic preservation, I recognize the panic as a familiar response to the economic changes that have been shaping the city for 75 years. As city leaders have struggled to develop an economic anchor for downtown, the historical and cultural features of the city have drawn more enthusiastic visitors than the retail businesses meant to profit from them.

Concern for the Wanamaker organ speaks to the ongoing challenge of preserving urban landmarks that remain tied to a consumer economy.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA., CC BY-NC-SA

‘Greatest organ in the world’

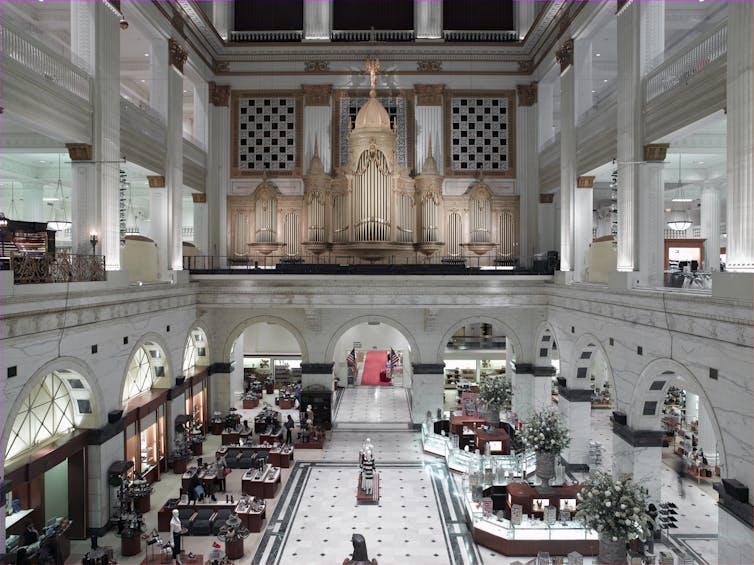

The visionary retailer John Wanamaker unveiled the organ to Philadelphians in 1911. Forty years after he had opened his first clothing store, he installed the organ as a showpiece of his new commercial palace’s seven-story Grand Court to add music and culture to the shopping experience.

A deep dive into the archives of The Philadelphia Inquirer shows how Philadelphians came to see the organ as a defining feature of the city’s historic character.

From its earliest days, advertisements touted the Wanamaker organ as “The Greatest Organ in the World.” Wanamaker had brought it from St. Louis, where it had debuted at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. News articles tracked the growing number of pipes, stops and circuits as Wanamaker and his son, organ aficianado Rodman Wanamaker, expanded the size and sound of the massive instrument. Increasingly elaborate decorations, including floral arrangements, fountains and artwork, transformed the organ into a visual spectacle as well.

The organ set Wanamaker’s apart from the city’s other well-known department stores. By the 1920s, the store hosted evening concerts that featured internationally renowned organists and attracted audiences of over 10,000 people.

In 1922, a radio station in the Wanamaker’s store engineered the first successful broadcast of an organ concert.

Heritage Images/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

‘Christmas isn’t Christmas without a day at Wanamaker’s!’

Though the annual holiday light show didn’t begin until the 1950s, Wanamaker’s made Christmas songs part of the organ’s repertoire from the beginning.

In 1917, for instance, advertisements in The Philadelphia Inquirer announced that the Wanamaker organist would play Yuletide selections until the new year. A full-page newspaper ad announcing the opening of the 1938 Christmas season featured a description of the organ, a Madonna painting above the organ loft, and bells hanging above.

A holiday ad in 1949 declared “Christmas isn’t Christmas without a day at Wanamaker’s!” It enticed visitors with “a memorable Christmas pageant,” with Christmas music played on the “famous” Wanamaker organ, illuminated with candles and surrounded by tableaux.

By 1953, an article about the organ’s history judged that “Philadelphians remember best how the organ’s music has been woven through the memories of countless Christmas seasons.”

Four years later, Wanamaker’s sought to cash in on this popularity by marketing an LP of Christmas songs played on the Wanamaker organ.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA., CC BY-NC-SA

A changing retail landscape

By the 1950s, however, downtown retail was in trouble. Wanamaker’s flagship store stood in the heart of what many consumers viewed as a declining city. Loss of manufacturing jobs, depopulation, political corruption, degrading urban infrastructure and perceptions of crime all threatened the commercial health of downtown.

Many shoppers favored new suburban shopping centers and indoor malls. Wanamaker’s catered to these shoppers by opening regional branches. Still, they struggled to compete with new retailers. New York stores such as Bloomingdale’s and Lord & Taylor offered high-end fashion and drew shoppers from wealthy suburbs. At the other end of the market, new discount retailers such as Clover and Caldor captured deal-seeking shoppers.

The Wanamaker organ became a gauge for how the store navigated this urban and retail change. In 1966, Wanamaker’s longtime organist and musical director Mary Vogt retired. Classical organ music had become passé, so Wanamaker’s hired 20-year-old music student Keith Chapman to infuse the standard repertoire with popular music and to host musical groups for performances with organ accompaniment.

The following year, new company president Edwin K. Hoffman ordered a management shake-up that ended the practice of playing the organ every morning at opening. Within a year, the Wanamaker family had fired him. Reportedly, the Wanamaker’s organist celebrated with an impromptu performance of “Happy Days Are Here Again.”

In this era, newspaper advertisements cast the Christmas program as a comforting bastion of Philadelphia tradition. Its “familiar Christmas carols” were part of the “time-proven formula and old familiar traditions” that remained intact at the store as the world changed around it.

New ownership

By 1974, Wanamaker’s was one of the few remaining family-owned department stores in the United States. Because the business remained silent about its bottom line, observers could only guess at its financial health. In 1974, a feature article in the Inquirer estimated that 100,000 people passed through the building each day. But it was unclear how many stopped to purchase something.

The health of the flagship store and the city were linked at a time of deepening economic downturn. In 1974, according to an Inquirer article from that year, Wanamaker’s employed 3,500 people at its Center City store and carried a tax burden of $20 million.

The company also had invested in the Market East urban renewal project to develop real estate, commerce and transportation in the neighborhood. Yet low office occupancy, shoplifting and the declining influence of corporate leaders in city affairs suggested that Wanamaker’s was far from thriving.

In 1978, the Wanamaker family sold its stores to Carter Hawley Hale Stores of Los Angeles. Multiple news articles from that period reveal how Philadelphians registered the new proprietor as a potential loss of local character and tradition.

Carter Hawley Hale became the first in a long string of retailers to face rumors that they were going to remove the organ or end performances. Carter Hawley Hale faced public backlash in 1982 when management reduced daily performances from three to two. In 1986, store proprietors showed a commitment to preserving the store’s historic character by writing a self-guided tour of the building.

When Federated Department Stores purchased Wanamaker’s in 1995, it immediately assured the public that the purchase agreement included a preservation clause for the Wanamaker organ. Managers of the stores that followed – Hecht’s, Lord & Taylor and Macy’s – made similar promises, newspaper archives show.

Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge via Getty Images

Historic preservation

When commercial uncertainty threatened the fate of the Wanamaker organ, citizens moved to secure its preservation.

Soon after the Wanamaker family sold its stores, the National Park Service named the building a National Historical Landmark in 1978. The organ received special attention as a defining historical feature. In 1991, local enthusiasts founded the Friends of the Wanamaker Organ nonprofit to raise money for an extensive restoration of the organ and its continued upkeep as a public treasure.

In 2018, the Philadelphia Historical Commission recognized the significance of the organ when it included it in the features of the Grand Court, one of only five interiors protected by provisions of the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. This means that new owners of the building will have to seek approval from the Historical Commission to alter or demolish the organ.

The Wanamaker building fell into receivership in 2023 after office tenants on the upper floors never returned in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. TF Cornerstone, a real estate company that in 2019 purchased the part of the building where Macy’s is housed, is reportedly in negotations to purchase the entire building. They plan to convert it into a mix of loft apartments, entertainment and fitness facilities, and smaller stores.

While the Wanamaker organ and Grand Court’s historic designation certainly make alterations and demolition more difficult, this doesn’t mean that they will be maintained and remain open to the public. As the author of Philadelphia’s interior preservation law explains, it will be up to City Council, the Historical Commission and the public to ensure such “demolition by neglect” does not take place.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Dec. 19, 2024.