After Kamala Harris selected Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as her running mate, much of the media coverage zeroed in on Walz’s Midwestern roots, with some pundits using the phrase “Minnesota nice” to describe his appeal.

In the popular imagination, Minnesota nice describes a culture of neighborliness and amicability that’s commonly seen as characteristic of the state. In policy terms, that might mean bigger investments in education, better public health, access to affordable housing and stronger worker rights – an extension of Walz’s achievements as Minnesota governor. Many Americans would probably like to see these values have primacy in the rest of the nation.

I think Minnesota nice, whether represented in policies or in being kind to neighbors, is a worthy ideal. But as someone who has studied the experiences of Vietnamese refugees in Minnesota, I’ve written about how the trope of Minnesota nice has a more complex history – especially when it comes to nonwhite people.

Rural origins

In her book “Creating Minnesota: A History from the Inside Out,” historian Annette Atkins suggests that the trope of Minnesota nice may have its roots in the state’s Scandinavian immigrants and the influence of the Lutheran church.

According to Atkins, Minnesota nice denotes “a polite friendliness, an aversion to confrontation, a tendency toward understatement … and emotional restraints.” These traits can be found in Scandinavian literature, film and art, as well as in 19th- and early 20th-century Lutheran values.

By the turn of the 20th century, 72% of Norwegian immigrants to Minnesota and 62% of Swedish immigrants to the state resided in rural areas. And one core element of Minnesota nice is the notion that residents are welcoming to strangers from other lands.

The arrival of Southeast Asian refugees

After the Vietnam War ended in April 1975, more than 120,000 Vietnamese refugees came to the U.S. Another wave followed in 1978. Their arrival was not universally welcomed by the American public.

To ease those concerns, government officials instituted a dispersal policy to spread out Southeast Asian refugees to ensure they wouldn’t be concentrated in any one region, town or city. They implemented this policy to reduce social and economic impacts on local communities – and also compel Southeast Asian refugees to assimilate into American culture.

In Minnesota, while many newcomers were given a helping hand, many of them also experienced isolation and rejection.

From 1979 to 1999, about 15,000 Vietnamese refugees arrived in Minnesota. My research shows that media outlets often ran articles highlighting the goodwill and generosity of locals, whether they were helping these refugees learn English, acquire job training, find work or secure housing.

The Minneapolis Tribune reported in 1975 that the state was able to avoid any major public reactions against refugees because they posed “no major job threat,” since they were spread out across the state.

Even as locals seemed largely supportive, the dispersal policy wasn’t ideal for many refugees. Many of them ended up in remote areas of Minnesota, far from a familiar ethnic community that could provide much-needed psychological and emotional support. Those in isolated areas often lacked access to social services and English language programs.

For refugees, a more complicated view of Minnesota nice emerges, one that I think depends on being not too visible and not too much of a threat to the existing order. Many refugees were certainly grateful for the state and local support they received. But gratitude also became an “unspoken condition” for acceptance, as Iranian refugee Dina Nayeri reports in her book “The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You.”

In Minnesota, locals could seem largely unsympathetic to the complicated struggles of refugees trying to settle in a strange, new land. Rather than complain, they ought to be happy for the “small blessings” they received, as one local St. Cloud resident wrote to the Minneapolis Tribune in 1975.

Bruce Bisping/Star Tribune via Getty Images

Minnesota too nice

When there was a sudden influx of refugees into one area, some residents could become even less welcoming.

That’s what happened with the state’s Hmong refugees.

An ethnic group originally from China, the Hmong arrived in Southeast Asia during the mid-19th century. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. government recruited the Hmong to fight in the Secret War in Laos, where the U.S. had been covertly providing aid and military assistance to anti-communist forces. After the war, some Hmong fled, fearing persecution. Many of them ended up in Minnesota. In 1980, there were about 2,000 Hmong people in Minnesota. By the end of 1981, their numbers had grown to 8,000, raising some alarm.

“Some cynics say our problem is that we are too nice and have provided too many services,” a local resettlement official was quoted saying in a 1980 State Department report. In that same report, an official with a local charity suggested that Minnesota would soon be known as “Hmong-nesota.”

In 1985, the Minnesota Star Tribune published a special report, “Hmong in Minnesota: Lost in the Promised Land,” that explored how many Hmong refugees had become “targets of racial epithets, harassment and violence” in the Twin Cities. The article noted that the Hmong came to realize that most Americans had never heard of them or their roles in the secret war in Laos. Instead, they often found themselves “resented, misunderstood and victimized by their neighbors.”

To me, the anxiety over “Hmong-nesota” recalled the history of “yellow peril” – the imagined threat of Asian invasion and cultural disruptions that first emerged in the 19th century and shaped many U.S. immigration policies.

Benevolence and violence

My own research explores how feel-good tropes that are prominent in the U.S., such as Minnesota nice, usually mask a more complicated story.

The U.S. government has often used the language of goodwill as a cover for violence – a phenomenon I call “bene/violence.”

For example, the U.S. occupation of the Philippines, which began in 1899, was sugarcoated in the rhetoric of benevolence. William McKinley, who was U.S. president at the time, insisted that “the strong arm of authority” would promote “the blessings of good and stable government upon the people of the Philippine Islands under the free flag of the United States.” The story of conquest became the story of “uplifting” those deemed less civilized and incapable of self-governance.

Forrest Anderson/Getty Images

The same sort of talk was also used to justify U.S. military intervention in Vietnam. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s State of the Union address on Jan. 4, 1965, implored Americans to secure the “peace of Asia” and “the progress of humanity.” The government promoted the war in Vietnam as a just war, in part by claiming Americans were granting the Vietnamese the “gift of freedom,” as Asian American studies scholar Mimi Nguyen has written.

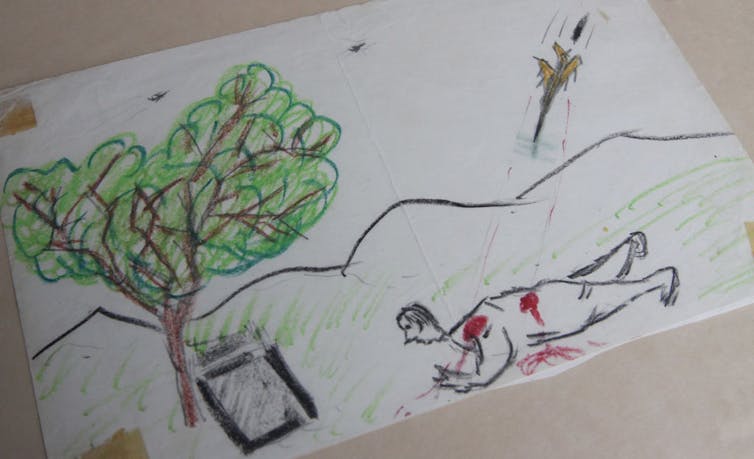

Of course, this version of events ignores the carpet bombing that killed as many as 1 million civilians. It overlooks the fact that 30% of Laos is still blanketed with 80 million unexploded bombs and other ordnance. And it forgets to mention how the extensive use of the toxic herbicide Agent Orange continues to scar the Vietnamese landscape and the country’s people.

The Minnesota paradox

In the end, Minnesota nice signals that there’s something special about the state, just as “spreading democracy” and “protecting freedom” signal American exceptionalism on the international stage.

But the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis illuminated what economist Samuel L. Myers calls the “Minnesota Paradox” – a history of inequality that is totally divorced from the way niceness operates in the cultural imagination of the state’s residents.

“African Americans are worse off in Minnesota than they are in virtually every other state in the nation,” Myers writes.

In a 2021 essay, sociologist Amy August also highlighted the state’s persistent racial disparities in housing, health care, income and education to argue that whatever progressive promises the state makes, Minnesota is not apart from America but rather a part of America.

Ultimately, I think the concept of Minnesota nice can create the illusion of a utopian society largely devoid of the ills of racism and inequality. It reinforces American kindness as a core aspect of national identity and, in doing so, I believe glosses over parts of the country’s history – while hampering its ability to address the very real problems that plague the nation today.

I don’t reject what Minnesota nice purports to offer. But it is not a simple and straightforward cultural value adopted by – and equally applied to – everyone.

![]()

Giang Nguyen-Dien does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.